Search

▼ House of Cards: Can Traditional New Year’s Greetings Survive in Modern Times?

- Category:Souvenir

JAPAN TIMES

On Jan. 1, legions of Japan Post Co. employees delivered millions of nengajō (New Year’s cards) to homes nationwide.

Over the next few days, employees at the postal company will sort through many more as they deal with a second wave of belated New Year’s cards in the post that have been sent by residents feeling pangs of guilt after receiving a greeting from someone who is not on their mailing list.

With more and more people communicating via social media, however, one has to wonder how much longer this annual New Year’s tradition will continue. According to Japan Post, New Year’s cards account for about 13.4 percent of all mail sent through the post over the course of a year.

Minoru Mitsuyama, section chief of the Stamps and Postcards Division at Japan Post, says the company dedicates plenty of resources to the delivery of New Year’s cards.

“New Year’s cards are definitely our main line of business,” Mitsuyama says. “People are accustomed to writing greetings on cards in the lead-up to the new year, and we are proud to help ensure they are delivered to their intended destination.”

While it’s perhaps too early to predict the demise of the New Year’s card, the numbers certainly don’t look good. Figures provided by Japan Post show that the number of New Year’s cards printed each year has dropped from its 4,459,360 peak in 2003 to just 3,301,732 in 2014, a drop of almost 26 percent. More worryingly, the record for the most number of New Year’s cards sold — 4,195,450 — was set way back in 1998.

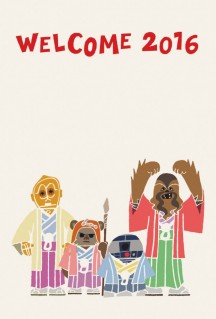

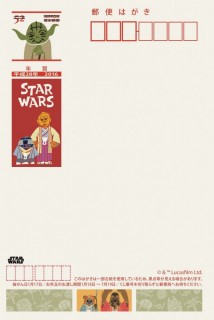

In a bid to halt the sharp drop in sales, Japan Post has tried to alter its approach in recent years, attempting to broaden its appeal to attract younger customers. In 2015, the postal company launched a new service called webu kyara (web character). The service allows customers to order printed cards from Japan Post that feature characters such as Hello Kitty, Cinderella, Snow White and “Star Wars” villain Darth Vader.

“The elderly and people who recently celebrated marriage, a newborn child or a new job will still send New Year’s cards, but younger customers who use smartphones don’t,” Mitsuyama says. “We wanted to show young people that sending New Year’s cards needn’t be so formal. We also wanted to remind them that sending cards wasn’t a hassle.”

Japan Post collaborated with convenience store Lawson Inc. in 2015 to test the waters for a new type of card that could be exchanged for the store’s premium roll cake. Naturally, the price was higher than that of normal cards — two for ¥490.

To encourage people to send New Year’s cards overseas, Japan Post has since 2014 been selling special ¥18 stamps that can be added to the ¥52 stamps already printed on cards, which enables cards to be the delivered anywhere in the world. The official ¥18 stamp for 2015 features images of ramen and sukiyaki.

Mitsuyama says the privatization of Japan’s postal service, a move spearheaded by then-Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi in 2005, has helped the company think outside the box.

“Since privatization, we’ve had much more freedom to work on projects (such as the collaboration with Disney),” Mitsuyama says. “I think this has been positive — we definitely have more of an awareness as a corporation, valuing both profit and customer satisfaction.”

Mitsuyama says the postal company is doing its best to increase sales figures.

“You cannot establish a tradition such as sending New Year’s cards overnight,” Mitsuyama says. “It’s a deep-rooted part of Japanese culture and many people continue to keep in touch via this once-a-year tradition. The country’s population is declining and we realize that we have a long road ahead. However, we want to target new customers.”

The origins of New Year’s cards is believed to go back about 1,000 years to the Heian Period (794-1185). A textbook on letters called “Oraimono” that was published around this time provides written instructions on how to construct New Year’s greetings, says Noriko Tominaga, curator at Postal Museum Japan in Tokyo’s Sumida Ward.

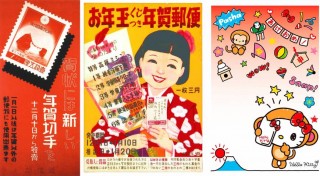

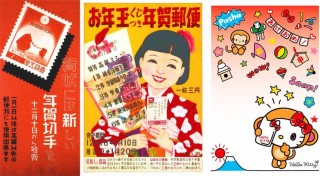

Through Jan. 11, the museum is hosting an exhibition on the history of New Year’s cards. A wide range of materials will be on display, including old advertising posters, various types of cards and a special collection of New Year’s stamps from Japan and around the world. The exhibit will also feature a number of colorful 2016 New Year’s cards that have been created to celebrate the Year of the Monkey.

“Of course, more people keep in touch with family and friends over the new year through email these days, but there is still a large number of people who continue to send New Year’s cards,” Tominaga says. “Some people might prefer to send messages electronically, but we want to show people that writing cards can be fun.”

Sending New Year’s cards was a tradition that was for a long time restricted to the upper class. However, literacy across the country improved during the Edo Period (1603-1868) after the terakoya private elementary schools taught writing and reading to the children of commoners, leading to an increase in the delivery of cards. The tradition was aided by the success of the hikyaku express delivery system that was established between Edo (modern-day Tokyo) and Kansai.

In fact, the cards became so popular that post offices began to struggle to process all the year-end mail in time. Indeed, post offices were forced to introduce a number of special measures to lessen the burden of delivery personnel — reducing the number of times a card is stamped by postal workers and creating a separate category for New Year’s cards that would encourage people to post them early — measures that remain in effect today.

World War II broke out and sending New Year’s greetings was put on the backburner as the nation went into a mood of restraint. Although there was no official ban on sending New Year’s cards, sales dropped drastically over the war years. The post office even stopped selling New Year’s stamps and discontinued the special delivery category. Both, however, were reinstated in 1948, three years after Japan’s surrender.

During this time of despair, one man came up with an idea that he believed would give people hope when searching for family or friends — New Year’s cards that were bundled with a lottery.

Masaji Hayashi, who ran a clothes shop in Osaka, apparently conceived the idea out of the blue one morning in June 1949. Naito references an interview with Hayashi in his 2011 book, “Nengajo no Sengoshi” (“The Postwar History of New Year’s Greeting Cards),” which was published by Kadokawa Corp.

The post office was impressed with his idea and petitioned the government to pass a law that would regulate the lottery, which it did later that year. Thus, official New Year’s cards have included a lottery number every year since 1950.

The first prize in 1950 was a sewing machine, while other prizes included cloth, children’s baseball gloves and umbrellas. The prizes have changed over time and have included such things as foldable bicycles, color TV, microwaves and video players. More recently, they have even included trips to Hawaii or other domestic destinations, laptop computers, washing machines and cash.

The exhibition at Postal Museum Japan features a complete list of the prizes that have been handed out.

In this way, New Year’s cards have become an inseparable part of Japanese culture. Naito believes the connection comes from the nation’s strong association with welcoming in the new year. Everything resets at the end of the year, he says, including the year-end tradition of ōsōji (big cleanup).

Naito notes that Japan didn’t celebrate individual birthdays until the Meiji Era. Until then, he says, everyone aged one year on Jan. 1. “The new year has so many special meanings in Japan,” Naito says. “It is embedded in our DNA.”

In fact, sending New Year’s greetings is considered so sacred that people who have lost a close family member in the past year are supposed to send mochū (mourning) cards instead. Etiquette requires such cards to be sent by early December at the latest, explaining that the sender will not be preparing New Year’s cards because they are in mourning.

However, Naito says, people in mourning can still receive New Year’s cards — a concept that is frequently misunderstood. Naito acknowledges that New Year’s card sales are certain to decline over time. Yet, he refuses to believe that the tradition will die out completely.

“New Year’s cards and letters are part of the culture,” Naito says. “They aren’t just communication tools. Writing a New Year’s card is the perfect way to convey a heartfelt message. This tradition will never disappear.”

- January 4, 2016

- Comment (0)

- Trackback(0)