Loading

Search

▼ Take a Sip of Japan!

- Category:Tourism

JAPAN GUIDE

Japanese Sake & Shochu Campaign

As part of the Japanese government's action program to promote tourism, the Tourism Agency and the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport have teamed up with four international airports and with the domestic alcohol industry to promote Japanese beverages such as sake, shochu, and awamori to international travelers to Japan.

As part of this campaign, they have set up booths in the duty-free areas of these airports where travelers can taste these traditional spirits and brews. The booths also offer information on types of drinks, their production, and which breweries are open to visitors. Explanations about traditional Japanese culture and other aspects of tourism are also available. The study of the different types of sake, shochu, and awamori that have been made in Japan is the task of a lifetime, but let this be a handy guide to get you started on that path.

Sake is known throughout the world as a distinctly Japanese drink. Though it is still often called "rice wine", the production of sake is far more similar to that of beer. Sake is brewed in breweries across Japan, every winter after the fall rice harvest.

The rice is then polished to various levels of fineness. The degree to which the rice is polished plays an important role in the flavor of the sake. Most sake produced in Japan is futsu-shu, or ordinary sake. Outside of the futsu-shu designation there is the type of sake called tokutei meisho-shu (special-designation sake).

The rice is then polished to various levels of fineness. The degree to which the rice is polished plays an important role in the flavor of the sake. Most sake produced in Japan is futsu-shu, or ordinary sake. Outside of the futsu-shu designation there is the type of sake called tokutei meisho-shu (special-designation sake).

This special-designation sake is further split up into many different types. The two main types are junmai-shu (sake made with only water, rice, yeast, and koji) and honjozo-shu (for which a small amount of brewer's alcohol is added to the fermenting sake). Sake is additionally classified based on the extent to which the rice was polished prior to fermentation.

The two main types are daiginjo-shu (sake made with rice polished to no less than half each grain's original size) and ginjo-shu (sake made with rice polished down to 60% or less than its original size). If the daiginjo or ginjo sake satisfies the requirements of junmai-shu, then it can be called either junmai daiginjo-shu or junmai ginjo-shu. There are also other special types of sake whose production involves specific requirements regarding fermentation and processing.

The two main types are daiginjo-shu (sake made with rice polished to no less than half each grain's original size) and ginjo-shu (sake made with rice polished down to 60% or less than its original size). If the daiginjo or ginjo sake satisfies the requirements of junmai-shu, then it can be called either junmai daiginjo-shu or junmai ginjo-shu. There are also other special types of sake whose production involves specific requirements regarding fermentation and processing.

Other sake of note are namazake, genshu, and nigorizake. Namazake is unpasteurized and requires refrigeration. Namazake has a youthful flavor, with more sharpness around the edges, making it an especially nice drink during springtime. Any type of sake can have a namazake version, so trying both the standard and the namazake is a fun way to find new flavors without switching breweries or brands. Genshu is a stronger sake.

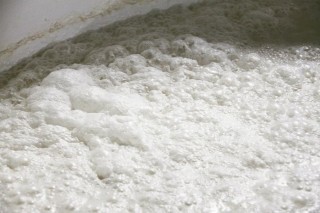

Water is normally added to sake before bottling to smooth out its flavor. Genshu production skips this step, which gives the sake a higher alcohol content. Genshu often has more of a kick and is usually served chilled or on ice. Nigorizake is an opaque white, while sake is typically clear. The cloudiness comes from the minimal filtration done when the sake is pressed after fermentation.

Nigorizake is often sweeter than most other sake types because of the leftover rice particulate. Nigorizake, namazake, and genshu are not mutually exclusive types, which means it is possible to have sake that is labeled as "junmai daiginjo genshu namazake" or "ginjo nama nigorizake". By knowing these different classifications of sake, it will become easier to determine and find the kinds of sake that you enjoy. For more information on sake types and sake in general, you can check out the JSS's English website.

Nigorizake is often sweeter than most other sake types because of the leftover rice particulate. Nigorizake, namazake, and genshu are not mutually exclusive types, which means it is possible to have sake that is labeled as "junmai daiginjo genshu namazake" or "ginjo nama nigorizake". By knowing these different classifications of sake, it will become easier to determine and find the kinds of sake that you enjoy. For more information on sake types and sake in general, you can check out the JSS's English website.

Shochu, unlike sake, is not only made from rice, but from a wide variety of different starches that each impart their own distinct flavor into the beverage. Rather than being a brewed drink, shochu is a distilled alcohol much like whiskey or rum. There are two types of shochu: korui (column-distilled) and otsurui (pot-distilled, single distillation). Otsurui is more commonly known in Japan as honkaku shochu or authentic shochu.

Almost all shochu that you will find at Japanese restaurants will be this later type, honkaku shochu. Compared to shochu made in a column or Coffey still, honkaku shochu has more variety in flavor and nose.

Because less of the aromatics from the base ingredients are lost during the distillation process, honkaku shochu is known for its greater range of flavors. While the three main bases are rice, sweet potato, and barley, there are over thirty different base ingredients that can be used for making shochu. Each of these ingredients imparts unique flavors into the drink, and each has its own recommended drinking style.

The three most common ways to drink shochu are: mixed with warm water, on the rocks, or in a chuhai. The word chuhai is a portmanteau of the words shochu and highball (highball in Japanese being pronounced haiboru). The drink usually consists of soda water and a generous serving of shochu along with a fruity sweetener.

Because less of the aromatics from the base ingredients are lost during the distillation process, honkaku shochu is known for its greater range of flavors. While the three main bases are rice, sweet potato, and barley, there are over thirty different base ingredients that can be used for making shochu. Each of these ingredients imparts unique flavors into the drink, and each has its own recommended drinking style.

The three most common ways to drink shochu are: mixed with warm water, on the rocks, or in a chuhai. The word chuhai is a portmanteau of the words shochu and highball (highball in Japanese being pronounced haiboru). The drink usually consists of soda water and a generous serving of shochu along with a fruity sweetener.

In general, barley-based shochu is the least distinctive of the big three, and has a light, punchy burn. Rice shochu has an all-around thicker taste with a bit more sweetness than either barley or sweet potato shochu. Sweet potato shochu incorporates a wide range of flavors, but for the most part is characterized by earthy tones. For beginners, most bartenders will recommend trying a barley- or rice-based shochu before trying the more complex flavors of a sweet potato blend.

Sweet potato shochu is far and away the most heavily-produced type of shochu, and the one with the largest variety in its flavor. In Kyushu, the birthplace of shochu, the word sake often will refer to shochu rather than the sake that is typical on the mainland. Depending on the ratio of the potato varietals and the aging process after distillation, potato shochu can taste earthy and dark like an Irish whisky, or light and refreshing like a mild gin. Many other types of shochu exist in Japan outside of the big three, and alcohol enthusiasts in particular will enjoy trying as many as they can to find the flavors that are right for them.

Sweet potato shochu is far and away the most heavily-produced type of shochu, and the one with the largest variety in its flavor. In Kyushu, the birthplace of shochu, the word sake often will refer to shochu rather than the sake that is typical on the mainland. Depending on the ratio of the potato varietals and the aging process after distillation, potato shochu can taste earthy and dark like an Irish whisky, or light and refreshing like a mild gin. Many other types of shochu exist in Japan outside of the big three, and alcohol enthusiasts in particular will enjoy trying as many as they can to find the flavors that are right for them.

Awamori, however, is unique in its position as being similar to shochu, yet also distinct at the same time. First made on the Okinawan islands in the 15th century, awamori and its main ingredient, indica rice, came to Okinawa from Thailand. Like shochu it is made through distillation but compared to shochu it has a spicier mouthfeel with a lingering floral aroma. This change in flavor comes from differences in the rice and from the fact that Awamori is often aged, which brings out different flavors than unaged shochu. For more information about shochu and awamori, check out the JSS's English website.

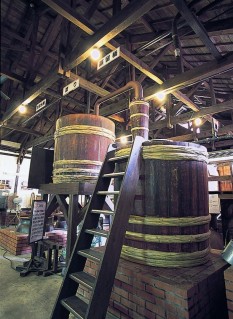

It's possible to tour many of the sake breweries and shochu distilleries in Japan. Visiting a brewery or distillery can give you a new appreciation for the craft of the brewer, and the tour often includes a tasting session. The brewers themselves will explain the different flavors that they have added to their drink and their recommended way to drink it. While there are distilleries and breweries close to the big cities of Tokyo and Osaka, many of the best breweries are spread throughout the countryside, where sake and shochu have been made the same way for generations.

It's possible to tour many of the sake breweries and shochu distilleries in Japan. Visiting a brewery or distillery can give you a new appreciation for the craft of the brewer, and the tour often includes a tasting session. The brewers themselves will explain the different flavors that they have added to their drink and their recommended way to drink it. While there are distilleries and breweries close to the big cities of Tokyo and Osaka, many of the best breweries are spread throughout the countryside, where sake and shochu have been made the same way for generations.

The Japan Sake and Shochu Makers Association has created apair of very useful sites to help you plan a visit to a sake brewery or a shochu distillery. These websites feature a comprehensive, searchable list of breweries and distilleries across Japan. They also contain information about brewery tours and each regional page has a bit of general information about each prefecture's food and traditional culture.

- November 9, 2018

- Comment (0)

- Trackback(0)