Search

▼ Okinawa: Always Worth Returning To

- Category:Tourism

JAPAN TIMES

The island of Okinawa shimmers beneath the wing of our plane, a dark green smudge on the azure seascape. I can’t see it well, ensconced as I am in the aisle seat, already subconsciously distancing myself from this visit. But my daughter, on the other end of the row, peers out the window with wide eager eyes, hungry for a glimpse of her first home.

Back in the summer of 2012, I bid an admittedly enthusiastic sayonara to the island I had called home for three years. My time on Okinawa was a challenging one. I never took to the oppressive humidity, the relentless typhoons, the many and prolonged absences of my husband that his job had entailed. Yet, somewhere in the middle of it all, a child was born. A blond-haired, full-blooded American girl who would leave the island as a toddler but who’d remain in Japan, growing increasingly curious of her adopted culture. And who would one day, inevitably, show interest in the island of her birth.

It is (mostly) for her that I am now suffering through this homecoming to my own personal subtropical hell. Yet, even as the sweat starts running into my eyes as soon as I exit the blessedly air-conditioned airport, I find myself excited to see the island again, through her eyes.

Those eyes lately seem fixated on all things “princess-related” so it only seems logical to start with a bit of royalty. We swing north out of the airport in our zippy little rental car and shoot across the cement-block city of Naha to the Shuri district to visit the castle.

Before that, however, there’s food to consider and we find it — in abundance — just past the rain-speckled orchids that frame the entrance to Ashibiuna. A large tour party clogs the polished hallway of the 70-year-old house-turned-eatery, but we’re led out onto the quiet veranda, where flitting butterflies outnumber the diners. Our table overlooks a garden with an identity crisis. The foreground is all rock, arranged in carefully raked concentric circles, while behind the stones, orchids and hibiscus flowers compete colorfully for attention in a haphazard array. A stone lantern sits not too far from a ceramic shisa lion, a nod to both mainland and island culture. We sip our shikuwasa (Okinawan lime) juice as a seasonal shower passes through, offering a few minutes’ respite from the relentless humidity. My daughter, bored with her airplane toy, holds court on the porch as she dances to the sanshin (three-stringed lute) music piped throughout the property. I know she has no conscious memory of the eisa dancers that once practiced around the corner from our home, but her movements mimic their gestures all the same.

Our hungry youngster is a fast fan of tofu champuru, a dish that simply means “mixed all together” in the local uchinaguchi dialect and usually includes bean sprouts and a few other vegetables. I get the goya version, loaded with slices of the island’s abundant bitter gourd. My first taste of the much-maligned vegetable years ago was less than inspiring; now, I give it the same second chance I’ve allotted its birthplace and find that it’s a cinch to clean my plate this time around. We end with a tiramisu made from beni-imo, the vividly purple Okinawan sweet potato that is packed with antioxidants and utilized in just about every dessert imaginable on island. This incarnation is one of my favorites yet; we all playfully elbow each other as we scrape the bowl for any last vestiges of the slightly tangy cream.

Feeling fortified, we make the long walk along Shuri Castle’s outer walls to reach the main entrance on the southern end of the complex. Just past the Shureimon Gate, a colorful portal initially built in 1555, my daughter spots her first princesses among the costumed staff. I hurry her along with the promise of more, hoping we’re not too late to catch the traditional dance performances up at the una, the castle’s open square.

We manage to witness the final minutes of the afternoon dances on the makeshift stage in the sprawling courtyard before turning our attentions to the seiden (chief royal residence). On my last visit here, the exterior was wrapped up tight in construction scaffolding. Today, the newly repainted beams provide a bold contrast to the blue sky overhead. Inside also seems to gleam, and even the second-foor throne room looks recently polished. The gold and vermilion dragons that flank the reconstructed seat of power fairly sparkle. My daughter deems the gilded chair perfect for a princess; generations of Ryukyu emperors certainly agreed. From their perch, surrounded by calligraphy inscriptions hand lettered by Chinese emperors of the Middle Ages, they would welcome trade envoys, host royal banquets or slide their dais forward to look down on gatherings in the una below.

After retracing our steps around the rambling castle walls once more, we find refuge from the unabating humidity in the Karisanfan Tea House. Despite my three-year tenure here, I never once heard mention of Okinawa’s famous bukubukucha, or bubbly tea. I’m curious to compare this favored treat of the Ryukyu royals to the typical cup of cha from mainland.

“A long time ago, people would drink bukubukucha at most major events,” explains Okinawan-born Tsukiko Mitsuboshi, as she seats us on a sarong-strewn bench in the incense-perfumed eating area. “Moon viewing parties, weddings and oiwai (meetings to arrange marriages) were particularly popular occasions for the tea.”

Around a century ago, however, bukubukucha seemed to fall off the cultural radar and the widespread bombing of the island during World War II resulted in the destruction of nearly every single original tea set. With much of the next few postwar decades devoted to reconstruction and reclamation of the island from U.S.-government control, a resurgence of Ryukyu culture wasn’t really seen until around 20 years ago. Mitsuboshi’s teahouse has been whipping up the frothy tea for the past 17 years, a pioneer in reintroducing bukubukucha to the masses.

Having taken our orders, Mitsuboshi brings out a large wooden bowl with a tea whisk thrice the size of the instrument used in mainland chado tea ceremonies. “Beat around the edges to build up the bubbles,” she demonstrates, and says the longer we let the froth sit, the harder it will become.

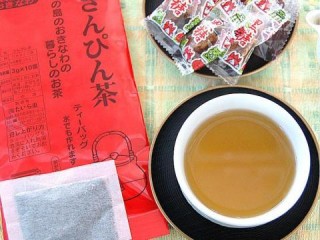

We all take a turn at the whisk, lathering the liquid into a copper-colored foam. The mixture is a combination of sanpincha (brown tea) and Okinawan water. Ranking high in many different minerals, the island’s hard water is the essential ingredient that causes the foam. It’s the main reason the tea can’t be replicated elsewhere.

My husband orders a coffee that comes with an already-whipped 15-cm tower of froth on the cup. I sip my getto-cha (made from the island’s shell ginger plant) topped with our own bubbly efforts, trying to determine if it’s the drink or the airy topper that tastes a tad bitter. Thankfully, I can soothe my palette with the range of Okinawan sweets Mitsuboshi provides. While my daughter reaches immediately for the standard chinsuko (Okinawan cookies made with lard), I bag the cake-like konpen. As with the tea, this sesame-paste snack is a first for me, but a few bites in, I’m already vowing to track it down in a local shop.

As we leave, I query Mitsuboshi on the name of her shop.

“These kanji here,” she says pointing to the tea house’s name, “are the Okinawan word for lucky, or happy.”

Fitting, I think to myself as we walk out the door, since that is exactly how I am feeling about this Ryukyu return. Perhaps you can go home again after all.

- September 24, 2015

- Comment (0)

- Trackback(0)