Loading

Search

▼ 5 Years on, Abe Continues to Dominate Party, Bureaucrats

- Category:Other

Tuesday marks five years since the launch of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s second Cabinet in December 2012. Giving top priority to the economy, Abe has steadily been strengthening his political base as the predominant force within the Liberal Democratic Party.

However, the government is only halfway along the path toward overcoming deflation. Meanwhile, Abe is eager to stay in power even longer to realize his long-cherished dream of constitutional amendment.

Over the past five years since Abe returned to power in 2012, he has consistently insisted on giving top priority to the economy.

In the House of Representatives election in October, where the ruling LDP marked its fifth consecutive victory in national elections, Abe pledged to accelerate his Abenomics economic policy package. On Friday, the benchmark 225-issue Nikkei average closed at 22,902 on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, about 2.2 times its level around the time Abe returned to power.

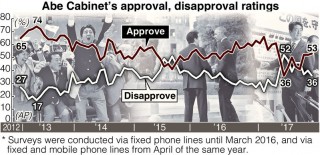

As if in tandem with high stock prices, Abe has maintained high approval ratings, based on which he has exercised strong leadership.

But while Abe emphasizes strong economic data, the public has not felt an economic recovery.

In a Yomiuri Shimbun nationwide survey in November, 62 percent of respondents wanted Abe’s Cabinet to give priority to the economy and job security. This is apparently because the “virtuous economic cycle” envisioned by Abe has not been realized, as strong corporate performances have not directly led to wage hikes for company employees and others. Abe is also sensitive to the subject of wage hikes.

Another cause of concern is whether to raise the consumption tax rate from 8 percent to 10 percent in October 2019. Abe has already postponed the consumption tax rate hike twice. If he delays it again, it would become even more difficult to restore fiscal health, which would inevitably trigger criticism of the failure of Abenomics.

Diplomacy

Along with the economy, head-of-state diplomacy is another driving force behind Abe’s handling of the government.

Among the leaders of the Group of Seven industrialized countries, Abe is the second longest-serving leader after German Chancellor Angela Merkel. “The strong public confidence in the Cabinet gives me great strength in diplomacy,” Abe said, showing his self-confidence.

The Japan-U.S. alliance has also deepened. Just after Abe’s second Cabinet was inaugurated, it could not be said that Japan and the United States were on good terms. For example, in 2013, the United States expressed disappointment about the prime minister’s visit to Yasukuni Shrine.

However, the government is only halfway along the path toward overcoming deflation. Meanwhile, Abe is eager to stay in power even longer to realize his long-cherished dream of constitutional amendment.

Over the past five years since Abe returned to power in 2012, he has consistently insisted on giving top priority to the economy.

In the House of Representatives election in October, where the ruling LDP marked its fifth consecutive victory in national elections, Abe pledged to accelerate his Abenomics economic policy package. On Friday, the benchmark 225-issue Nikkei average closed at 22,902 on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, about 2.2 times its level around the time Abe returned to power.

As if in tandem with high stock prices, Abe has maintained high approval ratings, based on which he has exercised strong leadership.

But while Abe emphasizes strong economic data, the public has not felt an economic recovery.

In a Yomiuri Shimbun nationwide survey in November, 62 percent of respondents wanted Abe’s Cabinet to give priority to the economy and job security. This is apparently because the “virtuous economic cycle” envisioned by Abe has not been realized, as strong corporate performances have not directly led to wage hikes for company employees and others. Abe is also sensitive to the subject of wage hikes.

Another cause of concern is whether to raise the consumption tax rate from 8 percent to 10 percent in October 2019. Abe has already postponed the consumption tax rate hike twice. If he delays it again, it would become even more difficult to restore fiscal health, which would inevitably trigger criticism of the failure of Abenomics.

Diplomacy

Along with the economy, head-of-state diplomacy is another driving force behind Abe’s handling of the government.

Among the leaders of the Group of Seven industrialized countries, Abe is the second longest-serving leader after German Chancellor Angela Merkel. “The strong public confidence in the Cabinet gives me great strength in diplomacy,” Abe said, showing his self-confidence.

The Japan-U.S. alliance has also deepened. Just after Abe’s second Cabinet was inaugurated, it could not be said that Japan and the United States were on good terms. For example, in 2013, the United States expressed disappointment about the prime minister’s visit to Yasukuni Shrine.

However, after Japan passed into law the security-related legislation to allow the limited exercise of the right of collective self-defense, the bilateral relationship was strengthened.

In 2016, former U.S. President Barack Obama visited atomic-bombed Hiroshima, while Abe paid a memorial visit to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, with Obama, the first joint visit by both the Japanese and U.S. leaders. Abe has also established a personal relationship of trust with incumbent U.S. President Donald Trump.

Even so, some issues remain. With the situation surrounding North Korea becoming increasingly tense, Trump, who visited Japan for the first time in November, is somewhat isolated in the international community.

A source close to the Japan-U.S. diplomacy said, “How to distance itself from the U.S. government will become a difficult challenge in the future for the Japanese government.”

Constitutional revisions

For Abe, who has been actively managing the government with a focus on the economy and diplomacy, the largest remaining issue is constitutional amendment.

Under Abe’s first Cabinet (from September 2006 to September 2007), the national referendum law providing procedures for amending the Constitution was established. Abe calls the law a “bridge” toward constitutional amendment.

Abe previously resigned as prime minister in disappointment. But there is no doubt that the force that drove Abe to return to power in 2012 was “his determination to cross the bridge of constitutional amendment,” according to an aide close to the prime minister.

Five years ago, when Abe’s Cabinet was inaugurated, the ruling bloc did not hold a majority in the House of Councillors. However, it successively won upper house elections in 2013 and 2016, while enjoying a sweeping victory both in the 2014 and 2017 lower house elections.

Through these elections, the ruling parties secured two-thirds of seats in both chambers of the Diet, majorities that are necessary for initiating constitutional amendment, and Abe succeeded in putting the issue of constitutional amendment on the political agenda.

However, discussions on the issue between ruling and opposition parties did not progress as Abe anticipated.

In an interview with The Yomiuri Shimbun in May, Abe daringly expressed his goal of “amending the Constitution in 2020,” apparently because he was exasperated by the slow progress in the discussions between them.

“While I caused a stir, the controversy was too big, and we had a hard time after that,” Abe recalled in a speech on Dec. 19. However, the LDP compiled points of contention for constitutional amendment earlier this month, and discussions within the LDP are becoming active.

On Tuesday, the number of days Abe has stayed in power will reach 2,193, including the period of his first Cabinet, and he is now eying the possibility of becoming Japan’s longest-serving prime minister.

Under the longtime rule of a government that will last until 2021, the year 2018 will be a year of challenge for Abe, who aims to translate his long-cherished dream into a reality.

Stable executive lineup

When it comes to personnel affairs, Abe prioritizes stability and tries to avoid as much as possible failures that could shake the government. Relying on high Cabinet approval ratings, Abe has control over bureaucrats in the Kasumigaseki district of Tokyo.

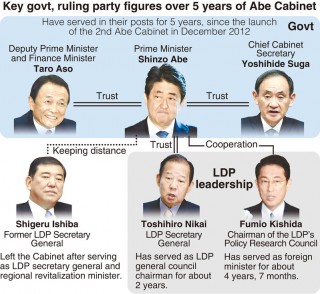

Since the launch of Abe’s second Cabinet in December 2012, Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Taro Aso and Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga have stayed in their respective positions.

Suga works to contain anti-Abe forces within the LDP.

Suga recommended that Abe appoint lawmakers close to Shigeru Ishiba, the former LDP secretary general who distanced himself from Abe, as Cabinet members. Suga’s proposal materialized, which has caused Ishiba’s influence within the party to decline.

The appointment of top bureaucrats requires Suga’s approval. Aso also became the leader of the second-largest faction within the LDP.

“Without those two, who are the backbone of the government, the past five years would have been different,” an aide close to Abe said.

There is also only a small number of lawmakers who express opposition to LDP Secretary General Toshihiro Nikai, the party heavyweight who leads the Nikai faction. By assigning LDP Policy Research Council Chairman Fumio Kishida, who is seen as the most likely candidate to succeed Abe, to an important post, Nikai has also established a good relationship with the Kishida faction.

Meanwhile, there is smoldering dissatisfaction about policy decisions led by the Prime Minister’s Office.

“Arrogance” could be Abe’s Achilles heel. He repeatedly made provocative remarks in the Diet regarding the Moritomo Gakuen and the Kake Educational Institution.

Abe dissolved the lower house at the outset of the extraordinary Diet session that was convened in September, and postponed discussions for several bills at the special Diet session that was convened in November. As a result, the Diet sessions lasted only 190 days this year, the shortest in 21 years.

There is deep-rooted criticism, as Kiyomi Tsujimoto, the Diet affairs committee chairwoman of the opposition Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan, said, “I want [the prime minister] to ensure sufficient debates without avoiding them.”

In 2016, former U.S. President Barack Obama visited atomic-bombed Hiroshima, while Abe paid a memorial visit to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, with Obama, the first joint visit by both the Japanese and U.S. leaders. Abe has also established a personal relationship of trust with incumbent U.S. President Donald Trump.

Even so, some issues remain. With the situation surrounding North Korea becoming increasingly tense, Trump, who visited Japan for the first time in November, is somewhat isolated in the international community.

A source close to the Japan-U.S. diplomacy said, “How to distance itself from the U.S. government will become a difficult challenge in the future for the Japanese government.”

Constitutional revisions

For Abe, who has been actively managing the government with a focus on the economy and diplomacy, the largest remaining issue is constitutional amendment.

Under Abe’s first Cabinet (from September 2006 to September 2007), the national referendum law providing procedures for amending the Constitution was established. Abe calls the law a “bridge” toward constitutional amendment.

Abe previously resigned as prime minister in disappointment. But there is no doubt that the force that drove Abe to return to power in 2012 was “his determination to cross the bridge of constitutional amendment,” according to an aide close to the prime minister.

Five years ago, when Abe’s Cabinet was inaugurated, the ruling bloc did not hold a majority in the House of Councillors. However, it successively won upper house elections in 2013 and 2016, while enjoying a sweeping victory both in the 2014 and 2017 lower house elections.

Through these elections, the ruling parties secured two-thirds of seats in both chambers of the Diet, majorities that are necessary for initiating constitutional amendment, and Abe succeeded in putting the issue of constitutional amendment on the political agenda.

However, discussions on the issue between ruling and opposition parties did not progress as Abe anticipated.

In an interview with The Yomiuri Shimbun in May, Abe daringly expressed his goal of “amending the Constitution in 2020,” apparently because he was exasperated by the slow progress in the discussions between them.

“While I caused a stir, the controversy was too big, and we had a hard time after that,” Abe recalled in a speech on Dec. 19. However, the LDP compiled points of contention for constitutional amendment earlier this month, and discussions within the LDP are becoming active.

On Tuesday, the number of days Abe has stayed in power will reach 2,193, including the period of his first Cabinet, and he is now eying the possibility of becoming Japan’s longest-serving prime minister.

Under the longtime rule of a government that will last until 2021, the year 2018 will be a year of challenge for Abe, who aims to translate his long-cherished dream into a reality.

Stable executive lineup

When it comes to personnel affairs, Abe prioritizes stability and tries to avoid as much as possible failures that could shake the government. Relying on high Cabinet approval ratings, Abe has control over bureaucrats in the Kasumigaseki district of Tokyo.

Since the launch of Abe’s second Cabinet in December 2012, Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Taro Aso and Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga have stayed in their respective positions.

Suga works to contain anti-Abe forces within the LDP.

Suga recommended that Abe appoint lawmakers close to Shigeru Ishiba, the former LDP secretary general who distanced himself from Abe, as Cabinet members. Suga’s proposal materialized, which has caused Ishiba’s influence within the party to decline.

The appointment of top bureaucrats requires Suga’s approval. Aso also became the leader of the second-largest faction within the LDP.

“Without those two, who are the backbone of the government, the past five years would have been different,” an aide close to Abe said.

There is also only a small number of lawmakers who express opposition to LDP Secretary General Toshihiro Nikai, the party heavyweight who leads the Nikai faction. By assigning LDP Policy Research Council Chairman Fumio Kishida, who is seen as the most likely candidate to succeed Abe, to an important post, Nikai has also established a good relationship with the Kishida faction.

Meanwhile, there is smoldering dissatisfaction about policy decisions led by the Prime Minister’s Office.

“Arrogance” could be Abe’s Achilles heel. He repeatedly made provocative remarks in the Diet regarding the Moritomo Gakuen and the Kake Educational Institution.

Abe dissolved the lower house at the outset of the extraordinary Diet session that was convened in September, and postponed discussions for several bills at the special Diet session that was convened in November. As a result, the Diet sessions lasted only 190 days this year, the shortest in 21 years.

There is deep-rooted criticism, as Kiyomi Tsujimoto, the Diet affairs committee chairwoman of the opposition Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan, said, “I want [the prime minister] to ensure sufficient debates without avoiding them.”

- December 25, 2017

- Comment (0)

- Trackback(0)