Loading

Search

▼ Japan Blasted A Hole In An Asteroid. Now Its Going To Try And Land There

- Category:Other

What if we could look back in time 4.5 billion years to the dawn of the Solar System? If all goes to plan, Japan's Hayabusa-2 spacecraft will attempt to do just that this week, and offer an unprecedented insight into not only the origin of the Solar System, but the origin of life on Earth.

On Thursday, July 11, the Hayabusa-2 spacecraft from the Japanese Space Agency (JAXA) will try to scoop pristine material from the interior of the asteroid Ryugu, having blasted a hole in its surface earlier this year. The daring landing attempt will be taking place 290 million kilometers from Earth, with scientists across the world looking on eagerly at a mission like no other with mouthwatering implications.

“This is a first for history,” says Harold Connolly, a co-investigator on Hayabusa-2 and also on NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission, a comparable asteroid sampling mission taking place elsewhere in the Solar System (the two teams will swap some samples when both return to Earth). “The material from underneath may have never been exposed to the surface, and will have preserved the history [of the asteroid] from 4.567 billion years ago.”

This will be Hayabusa-2’s second landing on Ryugu, another first in our spaceflight history – no spacecraft has ever intentionally landed on the surface of another world more than once. Its first landing occurred in February 2019, when it’s believed the spacecraft successfully collected a sample from the asteroid by firing a bullet into the surface along a meter-long sampling arm to kick up material into a collector.

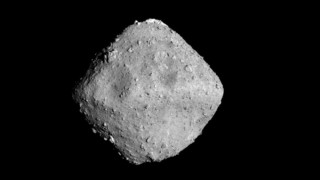

The spacecraft has been orbiting Ryugu, a carbon-rich asteroid measuring about one kilometer across, since June 2018 (dropping multiple landers later that year) having launched from Earth in December 2014. It is the successor to the troubled but ultimately successful Hayabusa-1 mission, which returned samples from another asteroid – Itokawa – in 2010.

This time around Japan is aiming for multiple samples of a much larger size.

Hayabusa-1 encountered problems with its sample mechanism and only returned with a few tiny grains from a single site on Itokawa. Hayabusa-2, on the other hand, is aiming for 0.1 grams of material from two separate sites.

However, there’s no way of knowing for sure if it has been successful until the spacecraft returns to Earth in late 2020, as its collector lacks any mechanism to detect a sample. So far the team can only rely on images taken during the maneuvers, which appear to show sufficient material being kicked up to reach the collector at least in the first landing.

On this second touchdown, the landing process will be largely the same. Hayabusa-2 will begin its descent to Ryugu on Wednesday, July 10 at 11 A.M. local time in Japan (10 P.M. Eastern Time on Tuesday, July 9). It is scheduled to reach the surface of the asteroid exactly 24 hours later on July 11, touching down at 11 A.M. local time in Japan (and the action will be streamed live on JAXA's YouTube channel).

This time around Japan is aiming for multiple samples of a much larger size.

Hayabusa-1 encountered problems with its sample mechanism and only returned with a few tiny grains from a single site on Itokawa. Hayabusa-2, on the other hand, is aiming for 0.1 grams of material from two separate sites.

However, there’s no way of knowing for sure if it has been successful until the spacecraft returns to Earth in late 2020, as its collector lacks any mechanism to detect a sample. So far the team can only rely on images taken during the maneuvers, which appear to show sufficient material being kicked up to reach the collector at least in the first landing.

On this second touchdown, the landing process will be largely the same. Hayabusa-2 will begin its descent to Ryugu on Wednesday, July 10 at 11 A.M. local time in Japan (10 P.M. Eastern Time on Tuesday, July 9). It is scheduled to reach the surface of the asteroid exactly 24 hours later on July 11, touching down at 11 A.M. local time in Japan (and the action will be streamed live on JAXA's YouTube channel).

The spacecraft will approach the asteroid at a final speed of a few centimeters per second. It will then briefly contact the surface, firing its projectile into the ground, before quickly ascending and taking about half a day to return to its home position 20 kilometers above the asteroid. “The difficulty of the second touchdown is almost same as that of the first one,” says Makoto Yoshikawa, the mission manager for Hayabusa-2. “The sample collection is the same.”

Of course, the major difference this time around is the nature of the sample itself. Hayabusa-2’s first sample was taken directly from the surface. While scientifically interesting, it is likely this sample has been irradiated by solar wind and cosmic rays throughout the asteroid’s history, changing its characteristics. So when designing the mission, JAXA decided to also attempt collecting material from beneath the surface.

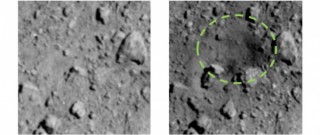

On April 4, the spacecraft released an impactor called the Small Carry-on Impactor (SCI), a 2.5-kilogram projectile fired towards the asteroid, to form a crater. Images released after the event showed the impactor had successfully formed a small deformation on the surface, measuring about 20 meters across. In so doing, material that had been hidden underground was also kicked out onto the surface.

Of course, the major difference this time around is the nature of the sample itself. Hayabusa-2’s first sample was taken directly from the surface. While scientifically interesting, it is likely this sample has been irradiated by solar wind and cosmic rays throughout the asteroid’s history, changing its characteristics. So when designing the mission, JAXA decided to also attempt collecting material from beneath the surface.

On April 4, the spacecraft released an impactor called the Small Carry-on Impactor (SCI), a 2.5-kilogram projectile fired towards the asteroid, to form a crater. Images released after the event showed the impactor had successfully formed a small deformation on the surface, measuring about 20 meters across. In so doing, material that had been hidden underground was also kicked out onto the surface.

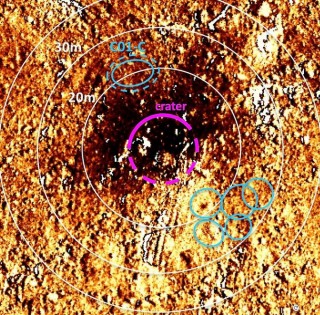

JAXA then took some time deciding whether to attempt a landing at this location. They had already dropped the idea of a third landing on the asteroid, fearing an increased risk of attempting too many landings. But in late June 2019, they decided to go ahead with the daring mission to this artificial crater.

The landing site, known as C01-C, is about 20 meters above the center of the impact, where material is believed to have been spewed onto the surface. The landing zone measures about 3.5 meters across, only slightly larger than the designated zone for the first landing at three meters.

Now the team will prepare to slowly lower the spacecraft in the coming days. If for any reason they need to abort, a second landing attempt will be made in the week of July 22. After that, the asteroid will be too close to the Sun, and thus too active, for a landing attempt. Time is of the essence.

“After July it will no longer be possible to perform the touchdown,” says Stefania Soldini, a JAXA Research Associate in the Hayabusa-2 project team. “Therefore any delay in the current scheduled operation might result in no other chances to collect the subsurface samples.”

The landing site, known as C01-C, is about 20 meters above the center of the impact, where material is believed to have been spewed onto the surface. The landing zone measures about 3.5 meters across, only slightly larger than the designated zone for the first landing at three meters.

Now the team will prepare to slowly lower the spacecraft in the coming days. If for any reason they need to abort, a second landing attempt will be made in the week of July 22. After that, the asteroid will be too close to the Sun, and thus too active, for a landing attempt. Time is of the essence.

“After July it will no longer be possible to perform the touchdown,” says Stefania Soldini, a JAXA Research Associate in the Hayabusa-2 project team. “Therefore any delay in the current scheduled operation might result in no other chances to collect the subsurface samples.”

There are some notable concerns regarding the landing. On the first landing, unsettled dust from the asteroid caused a “mist” that has slightly covered the spacecraft’s optical sensors. These are crucial for operations at low altitudes near the asteroid, so the team will descend to the asteroid slightly faster than before.

Another factor is that the surface inside the impact crater is not smooth, with a depth of up to two meters. “This is dangerous for the spacecraft to touchdown inside the crater,” notes Yoshikawa. However, he adds that it’s not thought there could be any material itself that could damage the spacecraft, but other dangers remain. “There are still high risks related to this operation,” adds Soldini.

If JAXA can pull off this landing, it’s hard to overstate how scientifically important it could be. In December 2019 the spacecraft will leave the asteroid, returning to Earth in late 2020. Here, it will deploy a capsule containing both of the samples into Earth’s atmosphere for collection on the ground. This will give us material not just from two locations on the asteroid, something that’s in itself unprecedented, but pristine material from an asteroid's origin too for the first time in history.

“[The landing on Ryugu] will be a very interesting, scary, and important moment for this fascinating mission,” says Patrick Michel from the Côte d'Azur Observatory in France, a co-investigator on the mission. “It’s worth the risk as long as all measures will be taken to abort if something suspicious happens during the operation!”

Of particular note will be learning how the surface material has been affected by the aforementioned space weathering processes compared to the subsurface sample. “We want to understand how space weathering works for such kinds of bodies, which is still poorly understood,” says Michel.

The surface of the asteroid also seems to be fairly dehydrated, containing little water content, but it’s possible the asteroid is richer in water below its surface. Scientists will be eager to find out whether the whole asteroid is relatively dry, or if its surface has simply been scorched by heat from the Sun throughout its history.

This could have implications for other things too, such as the presence of organic matter (the building blocks of life) on asteroids. The JAXA team believes these samples from Ryugu could provide information about organic matter and water from before Earth was even formed. Perhaps asteroids even played a part in delivering such material to Earth.

“We think ‘life’ may be difficult to know from the material of Ryugu, but we hope we can get some information about the original material that would become life,” says Yoshikawa. “As for the water, we think we can get some information related to the origin of the water of Earth.”

Already there are some notable differences between the two landing sites. The material exposed by the crater is much darker than the surface material of the first landing site, for reasons that are not clear. Only when these samples are returned to Earth could we find out for sure, and answer some of our other burning questions.

All eyes now will be on the spacecraft in the run up to the proposed descent to the surface. Japan may have landed on an asteroid before, but the stakes now are higher than ever before.

The team has just weeks until a landing is no longer possible, and issues remain regarding the landing operations themselves. But if everything goes smoothly, we could soon have our hands on material from the dawn of the Solar System for the first time in history. “It’s pretty nerve-wracking,” says Connolly.

Another factor is that the surface inside the impact crater is not smooth, with a depth of up to two meters. “This is dangerous for the spacecraft to touchdown inside the crater,” notes Yoshikawa. However, he adds that it’s not thought there could be any material itself that could damage the spacecraft, but other dangers remain. “There are still high risks related to this operation,” adds Soldini.

If JAXA can pull off this landing, it’s hard to overstate how scientifically important it could be. In December 2019 the spacecraft will leave the asteroid, returning to Earth in late 2020. Here, it will deploy a capsule containing both of the samples into Earth’s atmosphere for collection on the ground. This will give us material not just from two locations on the asteroid, something that’s in itself unprecedented, but pristine material from an asteroid's origin too for the first time in history.

“[The landing on Ryugu] will be a very interesting, scary, and important moment for this fascinating mission,” says Patrick Michel from the Côte d'Azur Observatory in France, a co-investigator on the mission. “It’s worth the risk as long as all measures will be taken to abort if something suspicious happens during the operation!”

Of particular note will be learning how the surface material has been affected by the aforementioned space weathering processes compared to the subsurface sample. “We want to understand how space weathering works for such kinds of bodies, which is still poorly understood,” says Michel.

The surface of the asteroid also seems to be fairly dehydrated, containing little water content, but it’s possible the asteroid is richer in water below its surface. Scientists will be eager to find out whether the whole asteroid is relatively dry, or if its surface has simply been scorched by heat from the Sun throughout its history.

This could have implications for other things too, such as the presence of organic matter (the building blocks of life) on asteroids. The JAXA team believes these samples from Ryugu could provide information about organic matter and water from before Earth was even formed. Perhaps asteroids even played a part in delivering such material to Earth.

“We think ‘life’ may be difficult to know from the material of Ryugu, but we hope we can get some information about the original material that would become life,” says Yoshikawa. “As for the water, we think we can get some information related to the origin of the water of Earth.”

Already there are some notable differences between the two landing sites. The material exposed by the crater is much darker than the surface material of the first landing site, for reasons that are not clear. Only when these samples are returned to Earth could we find out for sure, and answer some of our other burning questions.

All eyes now will be on the spacecraft in the run up to the proposed descent to the surface. Japan may have landed on an asteroid before, but the stakes now are higher than ever before.

The team has just weeks until a landing is no longer possible, and issues remain regarding the landing operations themselves. But if everything goes smoothly, we could soon have our hands on material from the dawn of the Solar System for the first time in history. “It’s pretty nerve-wracking,” says Connolly.

- July 10, 2019

- Comment (0)

- Trackback(0)