Loading

Search

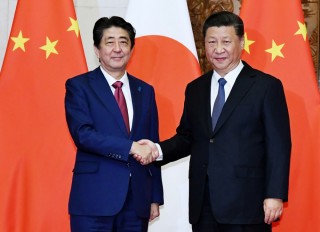

▼ How Xi and Abe can bridge China-Japan divide

- Category:Other

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe have much more in common than they may realize. Both come from elite political families with great influence within their respective countries.

Xi is considered a princeling within China because he is the son of Xi Zhongxun, who was one of the founding fathers of the People’s Republic of China. Abe is a third-generation politician, following in the footsteps of both his grandfather and his father.

Both men took over the top political job in their countries in late 2012. Xi succeeded Hu Jintao to be the general secretary of the Communist Party of China and Abe, who had served as prime minister from 2006-07, stormed back to the premiership in a landslide election victory.

Both have presided over assertive foreign policies since assuming office.

Xi spoke about a rejuvenated China and vowed to protect its core interests when necessary, and in 2013 he even declared an Air Defense Identification Zone in the East China Sea. Abe, for his part, vowed to amend the country’s pacifist constitution by 2020 and successfully pushed through a reinterpretation of the constitution’s Article 9 to give the Japanese Self-Defense Forces more leeway during combat.

With all that said, why have Japan and China, led by men who are quite similar, failed to develop a smooth relationship? The two countries’ relations have yet to be fully restored to what they were before the dispute over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands deepened. The recent rapprochement between Xi and Abe is more of a pragmatic move as both squared off with US President Donald Trump over trade policy.

Historically, the relationship between the two Asian neighbors has been colored by China’s bitter memories of Japanese occupation during World War II. However, they have since strived to keep the relationship on an even keel for the greater good.

But the nature of the relationship has changed since 2012, when the Japanese government moved to nationalize the Senkakus, which the Chinese call the Diaoyus, reawakening a dispute that had rumbled on relatively quietly for decades. The nationalization move serves to escalate the dispute significantly and laid the groundwork for today’s rocky relationship.

The governor of Tokyo at that time, Shintaro Ishihara, had announced plans to purchase the islands from their private owners and assert Japanese sovereignty over them. The central government was worried that he would incite a conflict with China and decided to pre-empt him by getting its own hands on the islands first.

What the government probably didn’t expect was the ferocity of the reaction from Beijing. China has claimed the islands as its own and named them Diaoyu Dao.

The nationalization move was widely seen in China as an insult, and no Chinese leader could afford to look weak in front of their domestic audience. A hardline stance toward Japan was the only plausible choice. And the nationalization of the islands came just before Xi’s ascension to power, and he could not afford to play nice.

In Japan, the aversion to China resulting from its growing economic and military might has grown dramatically over the years, which provides fertile ground for right-wing leaders like Abe to thrive. He was left to deal with the Senkakus mess left by the previous Democratic Party of Japan government and he could not afford to back down in light of repeated Chinese incursions around the islands.

The Sino-Japanese relationship remained in a subdued state for years.

So how can Japan and China get out of this mess?

First, there are encouraging signs of a thaw in the relationship.

On April 24 in Beijing, Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) Secretary-General Toshihiro Nikai was warmly received by Xi. Nikai passed a letter from Abe to Xi that called for a fresh era in the Sino-Japanese relationship. The letter came against the backdrop of Abe’s own visit to China in October 2018, the first by a Japanese prime minister in six years. Xi also agreed to travel to Japan in June for the G20 summit.

While it is encouraging that the relationship has been warming again, this has happened in the past, but then the relationship went off track again. There is a need to ensure the relationship is put on the right track for the long term.

For the sake of the future of their countries and the region, Xi and Abe should muster the courage to build more goodwill between their countries and ensure the thaw in their relationship lasts.

Xi and Abe are both strongmen in their respective countries and only they have the political strength to take steps to restore the bilateral relationship.

China and Japan should continue to deepen economic interlinks with each other and cultural exchanges between their people to deepen people-to-people ties to promote mutual understanding.

Abe should emulate the example set by Emperor Emeritus Akihito in acknowledging the damage done by Japan during World War II.

Most Japanese don’t subscribe to the right-wing beliefs held by Abe’s conservative base. Abe can still respect the war dead in Japan without being associated with the Yasukuni Shrine. By doing so, he will give leaders in China and South Korea space to tone down their hardline stance toward Japan and set a new era of cooperation.

Abe should widen his political appeal to the center of Japanese politics, and by doing so, he will build an alternative source of power to leverage on and enable him to sustain this new approach should he opt for it without being held hostage to the right-wing base. Abe can secure a new legacy in Japan as the leader who has finally made peace with China. He wants to restore Japan to being a “normal” country and wants to enhance Japan’s security. But his move is fiercely opposed by neighboring countries.

The only reason China fiercely opposed Japan’s attempt to amend its pacifist constitution was that it still perceived Japan to be insufficiently apologetic for its crimes during World War II.

Unlike Japan, Germany came to terms with its World War II past and now has been accepted by its European neighbors. Germany is able to maintain a normal army and be accepted on the continent as a peer.

Improving the relationship with China is one indispensable component should Abe and his faction want to succeed in amending the Japanese constitution.

Xi, on the other hand, should do more to reassure Japan about its concerns over national security. Xi must be more mindful of how he has been exercising China power and how it has been perceived by neighboring countries. Building a moderate image in Japan will not give oxygen to the right-wingers to sustain their power in Japan. This will pave the way for moderate centrist leaders to assume prominence in Japanese politics.

Slowly but steadily, the relationship between the two countries can be restored one day. The future of the Sino-Japanese relationship depends on the countries’ leaders.

- May 16, 2019

- Comment (0)

- Trackback(0)