Loading

Search

▼ Fired Up About Gifu’s Pottery Industry

- Category:Other

JAPAN TIMES

Toki, a small town in Gifu Prefecture, 37 km from Nagoya, sits above a huge clay basin. Pottery has been made here since ancient times.

The world-famous Oribe style, which uses green copper glaze and bold painted designs was invented in Gifu more than 400 years ago. Then the province was called Mino and it supplied the whole of Japan with sake flasks, bottles, jars, dishes, bowls, cups, plates, teapots, vases, incense burners, inkstones, water droppers, tea ceremony implements and smoking paraphernalia.

Mino pottery, known as Minoyaki has four main types: Oribe; Shino, which has a milky white to orange glaze, sometimes with charcoal grey spotting; the yellow Ki-seto and the black Kuro-seto.

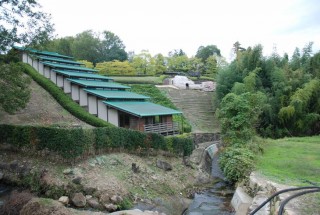

On the outskirts of Toki is Oribe Village Park where a 400-year-old kiln has been spectacularly preserved and another reconstructed. The

Motoyashiki Kiln had 14 firing chambers, now covered by a series of connecting pavilions cascading down a hill. Inside this unusual and intriguing structure there are preserved clay pots and plates, still waiting, readied for firing on many levels, just as they were one day centuries ago. They can be seen close-up from a long staircase.

This place is set in park-like grounds with flower gardens and there are various other attractions such as pottery workshops where visitors can make their own ceramics.

Although modern materials, such as plastic, have replaced a lot of ceramic production, the industry is still very much active in Toki. Among the town’s more than 100 ceramic companies, there are half a dozen nationally renowned potters. One of them, Masakazu Yamada, runs the White Mountain Kiln, founded by his great grandfather around 1900.

Born in Toki, he has worked as a potter for 51 of his 63 years.

Yamada gets commissions from all over Japan, supplying restaurants, hotels and department store exhibitions with plates, cups and vases, and making tiles for large ceramic murals. With regular customers, he often gets repeat orders — he never cold calls. As a member of the Japan Traditional Arts and Crafts Exhibition, an event held annually since 1954, he has also won nine prizes for best ceramic pieces between 1983 and 2014.

According to Yamada, the ceramics business boomed in the bubble years when he made only household utensils. Great quantities of Chinese industrially produced crockery, however, dented Japan’s domestic market, which led to him adapting to the new conditions by concentrating more on high-end artistic creations.

He puts a big lump of clay onto a wheel, explaining that he mixes light and heavy clay according to the type of plate or vase he now specializes in. Soon, with the addition of water and skilled handiwork, the clay is transformed into a tall, elegant vase, ready for drying and firing.

Inside one kiln are flower pots destined for Gifu’s venerable Suimeikan Hotel at Gero Onsen (regarded as one of Japan’s best hot-spring resorts).

Also, he shows some finished square plates of brilliant azure, green and brown glaze, destined for another hotel in the neighboring prefecture, Nagano. He tells me that he is paid ¥2,500 per plate through a middle man and gets a similar price for the flower pots, though he sells them direct to the Suimeikan.

Every November, there is a weekend fair in Orishi, a small town near Toki, when hundreds of potters from miles around set out their wares on trestle tables along several long alleys. A popular event with local people, there is a lot of good-natured bargaining for plates, cups and curios.

At the last fair, two sisters, Yuka Hibino and Junko Maida, and a helper were doing a brisk trade from their stall. Their company, which is 50 years old, was started by their father, who has since died, they explain. A brother-in-law took over and it is now a full time job for the family. When asked if they enjoy the work, like Yamada, they speak of a tougher business environment nowadays.

“Making and selling ceramics is not a bad living, but it needs a lot of cash to run and there are not as many benefits as before,” Hibino says.

Traveling further out, a 45-minute train ride from Toki by train is Seto, whose kilns have the longest production history in Japan. The atmosphere of the town is quiet and provincial, with homely cafes and cool jazz coming from a second-hand store. Seto, however, has made glazed pottery since the eighth century and it is still a thriving ceramics production hub. Its 24-hour semi-automated factories make one-sixth of Japan’s ceramics, turning out household objects of all types, and the town’s main street is packed with shops displaying the varied products of its potters.

There is a booth near Owari-Seto Station that offers maps and leaflets in English about the town’s attractions, and galleries and fine pottery exhibitions abound in the town. A short distance from the station is the Seto Gura Museum, which houses two huge ground-floor shops selling tea and coffee pots, jugs, plates, china wind chimes, ceramic houses, locomotives, red post boxes in 10 sizes, horses, dogs, pigs, cats and huge opened-mouthed frogs.

There is also a spacious cafe featuring a large kiln inside it, with firewood stacked as if ready for use, while on the floor above there are pottery tools and displays on coal-fired lime kilns, factories, pottery shops and the town’s old station.

Heading back toward Toki, I stop at Tajimi, which has thrived on ceramics since the Meiji Era (1867-1912). From Toki, Tajimi is just a six-minute train ride, and the town’s business is proclaimed at the station by a huge, boldly executed ceramic mural with swirling designs.

A short distance away is Honmachi Oribe Street, named after the famous green-and-black pottery style. Before World War II, ceramics wholesalers, run as family companies, were numerous here. However, now only one house in the area, owned by the Yamamatsu family, survives by running its original business.

According to Hiroshi Eguchi, who has a ceramics and antiques shop in Honmachi Oribe Street, the decline in ceramics occurred because “large families used to entertain at home often, so there was a big demand for bowls, cups, dishes and other household utensils. Over time, however, families became smaller, they ate out more and the market shrank.”

Eguchi has sold antiques and ceramics for 17 years. His Tenchido shop was the first of its kind in the street and it wasn’t until a couple of years later that another one opened.

“It was a lonely street when I started, and I don’t want to brag but I was successful because I worked hard,” he says. “Also, I consider honesty important, not telling lies and offering good prices on attractively arranged pieces.”

His wares range from a small 200-year-old Edo Period (1603-1868) plate for ¥200 to another plate that, at more than 350 years old, sells for ¥15,000 and features an ofuke surface of green melted glass, which is created by putting pine-tree leaves in the furnace.

These prices can be far eclipsed by the creations of a famous 19th-century Tajimi potter, Enji Nishiura, who made unpainted underglaze blue

Western-style tableware and brightly decorated vases, cake dishes and lamp stands. His creations, exported to Europe and America, are much in demand today and one of his pieces can sell for ¥250,000, says Eguchi.

The gradual revival of Honmachi Oribe Street led others to new businesses, too. Restaurants, cafes and curio shops began to flourish.

“Oribe has now been successfully gentrified,” Eguchi says. Now there is even a ceramics and art gallery.

Eguchi explains that the newer demand for pottery has changed his customer base in the last six or seven years. Though, not in a way that he necessarily likes.

“There are many Chinese buyers now, and they buy in bulk, 10 to 20 pieces of ceramics, silverware, ivory iron kettles — things that will fetch high prices in China. They come in small groups, two or three times a month, but their shopping manners are very bad. They touch things roughly and once I had a jade snuff bottle stolen worth ¥10,000,” he says, explaining that he prefers to sell to those who buy for themselves. “I don’t like the trend. I want to sell only to people who love antiques.”

by Stephen Carr

Getting there:

Tokishi Station in Toki is a 43-minute train ride from Nagoya on the JR Chuo Rapid Line (¥760). Tajimi Station is six minutes from Tokishi Station via the Chuo Rapid Line (¥200). Owari Seto Station in Seto is 45 minutes from Tokishi Station via the Chuo Rapid, Aichikanjo Tetsudo and Meitetsu-Seto lines (¥770). To learn more about Gifu Prefecture, visit travel.kankou-gifu.jp/en.

- November 9, 2015

- Comment (0)

- Trackback(0)