Loading

Search

▼ Better Environment Eyed for Japanese Eels

- Category:Other

The Yomiuri Shimbun

Aiming to expand the habitat of Japanese eels (see below), a species believed to be in danger of extinction, the Environment Ministry intends to compile guidelines for improving the natural environment of rivers, it has been learned.

To restore the population of the species, the ministry plans to secure places where eels can hide themselves, and make it easier for eels to come and go between the sea and rivers.

This will be the first time for the ministry to establish such guidelines for a single fish species, sources said. It will soon establish an expert panel and plans to announce the guidelines in March next year.

The population of Japanese eels has been rapidly plummeting because of overexploitation of young fish and the deterioration of the environmental conditions in their habitats. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) designated Japanese eels as an endangered species in 2014.

The nation’s domestic catch of young Japanese eels surpassed 200 tons a year in the early 1960s, but has fallen to around 10 tons in recent years.

Ahead of the compilation of the guidelines, the ministry has conducted its first nationwide research on wild Japanese eels since fiscal 2014. It found eel habitats in most of the nation’s coastal areas except for those off Hokkaido and in the Sea of Japan off Aomori Prefecture.

In the course of the research, a total of about 250 eels were caught in six river systems, including Tonegawa river in the Kanto region, Aonogawa river in Shizuoka Prefecture, and Saigogawa river in Fukuoka Prefecture.

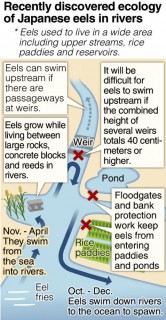

Ecological analysis of the fish revealed that nocturnal Japanese eels hide during daytime in spaces behind large stones on riverbeds and concrete blocks, and among plants such as reeds. The research showed that potential hideouts are important for the fish’s survival.

It also found that if there are many weirs to control the flow of a river, and if the combined height of two or more weirs exceeds 40 centimeters, it is difficult for the fish to swim to upstream areas. In places where there are movable weirs and fish-ways with gradual slopes, Japanese eels were able to move smoothly.

In the past, Japanese eels could be seen in rice paddies and reservoirs near rivers, but they became unable to move in and out partly because of bank protection works, and therefore disappeared from these places.

Based on the research results, the guidelines will likely include such preservation measures as easing the connections between the sea and rivers, and making it possible for the fish to move in and out of rice paddies and reservoirs, according to the sources.

Although the guidelines will not be legally binding, the ministry will ask river administrators and construction companies to give consideration to the preservation of Japanese eels when bank protection works and other projects are implemented.

An official of the ministry’s wildlife section said, “We want to quickly bring about river environments that are easier for Japanese eels to live in.”

■ Japanese eel

The fish lay eggs in the sea west of the Mariana Islands in the central-western part of the Pacific Ocean, and the young fish grow up mainly in rivers in coastal areas in East Asia for four to 15 years. They then return to the sea to spawn. In 2014, Japan, China, South Korea and Taiwan, which catch young Japanese eels for cultivation, agreed to set limits on the volume of their cultivation. However, some in other nations, including the United States and European countries, are calling for international regulations on trade in Japanese eels.

Aiming to expand the habitat of Japanese eels (see below), a species believed to be in danger of extinction, the Environment Ministry intends to compile guidelines for improving the natural environment of rivers, it has been learned.

To restore the population of the species, the ministry plans to secure places where eels can hide themselves, and make it easier for eels to come and go between the sea and rivers.

This will be the first time for the ministry to establish such guidelines for a single fish species, sources said. It will soon establish an expert panel and plans to announce the guidelines in March next year.

The population of Japanese eels has been rapidly plummeting because of overexploitation of young fish and the deterioration of the environmental conditions in their habitats. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) designated Japanese eels as an endangered species in 2014.

The nation’s domestic catch of young Japanese eels surpassed 200 tons a year in the early 1960s, but has fallen to around 10 tons in recent years.

Ahead of the compilation of the guidelines, the ministry has conducted its first nationwide research on wild Japanese eels since fiscal 2014. It found eel habitats in most of the nation’s coastal areas except for those off Hokkaido and in the Sea of Japan off Aomori Prefecture.

In the course of the research, a total of about 250 eels were caught in six river systems, including Tonegawa river in the Kanto region, Aonogawa river in Shizuoka Prefecture, and Saigogawa river in Fukuoka Prefecture.

Ecological analysis of the fish revealed that nocturnal Japanese eels hide during daytime in spaces behind large stones on riverbeds and concrete blocks, and among plants such as reeds. The research showed that potential hideouts are important for the fish’s survival.

It also found that if there are many weirs to control the flow of a river, and if the combined height of two or more weirs exceeds 40 centimeters, it is difficult for the fish to swim to upstream areas. In places where there are movable weirs and fish-ways with gradual slopes, Japanese eels were able to move smoothly.

In the past, Japanese eels could be seen in rice paddies and reservoirs near rivers, but they became unable to move in and out partly because of bank protection works, and therefore disappeared from these places.

Based on the research results, the guidelines will likely include such preservation measures as easing the connections between the sea and rivers, and making it possible for the fish to move in and out of rice paddies and reservoirs, according to the sources.

Although the guidelines will not be legally binding, the ministry will ask river administrators and construction companies to give consideration to the preservation of Japanese eels when bank protection works and other projects are implemented.

An official of the ministry’s wildlife section said, “We want to quickly bring about river environments that are easier for Japanese eels to live in.”

■ Japanese eel

The fish lay eggs in the sea west of the Mariana Islands in the central-western part of the Pacific Ocean, and the young fish grow up mainly in rivers in coastal areas in East Asia for four to 15 years. They then return to the sea to spawn. In 2014, Japan, China, South Korea and Taiwan, which catch young Japanese eels for cultivation, agreed to set limits on the volume of their cultivation. However, some in other nations, including the United States and European countries, are calling for international regulations on trade in Japanese eels.

- May 12, 2016

- Comment (0)

- Trackback(0)