Loading

Search

▼ Shoemaker Hidetaka Fukaya Models Creations on Feline Elegance

- Category:Experience

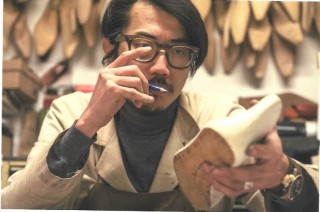

PIRAN, SLOVENIA – It’s easy to miss Hidetaka Fukaya’s bespoke shoemaking shop in the heart of Florence. “Il Micio” lurks in a narrow street in a tangle of other narrow streets, as if unwilling to call attention to itself. Just like a cat. And that’s fitting because Fukaya, recently named among Italy’s 100 best artisans by the Italia Su Misura website, takes his inspiration from feline elegance and independence — and, in fact, named his shop after the Italian word for kitty-cat.

“The cat is among the most beautiful creatures on Earth, both in form and movement,” Fukaya says. “And they don’t try to curry favor. The most important thing for me is to make customers happy, but as a craftsman it’s important to maintain my freedom of expression.”

It’s a philosophy that has helped Fukaya win respect and accolades in Italy’s secretive world of master craftsmen, with roots in Medieval guilds, in a city that is notorious for being one of the country’s most insular.

Today Fukaya commands prices of more than €3,000 (¥370,000) for a pair of made-to-order shoes, and creates readymade shoes for brands such as Japan’s Tomorrowland and Italy’s Tie Your Tie.

It has been a struggle reaching the top of his craft in a country that can be as tradition-bound as Japan. Fukaya was 24 when he left an enviable job in Tokyo as a designer for the Kensho Abe fashion label for the unknown world of fine Italian shoemaking. He did not speak a word of Italian.

The dream emerged by chance when he came across a book on Florentine artisans, and fell under the spell of the city’s shoemaking traditions. Since childhood, he had loved making things by hand — something he couldn’t do designing clothes — and suddenly decided that shoemaking was his calling.

“When I make a decision, I’m impatient to carry it out, that’s my personality — first just act, then think about it later,” Fukaya says. “So I just wanted to go to Italy, this feeling that I wanted to make shoes was so strong.”

But when Fukaya landed in Florence, there were no schools to teach him the craft. Today there are many Japanese studying Italian shoemaking — back in 1998, Fukaya was alone banging on the door of a closed-shop profession. He walked the streets of Florence, from shoemaker to shoemaker — a telephone book in hand — begging to be taken on as an apprentice. Each time the door was closed in his face. One day, a friend told him about the outstanding skill of a master shoemaker in the neighboring city of Siena. The encounter with Alessandro Stella’s handcrafted shoes, Fukaya recalls, was “love at first sight.” However, Siena is an even more insular city than Florence, and Stella refused to take Fukaya in. Undaunted, Fukaya kept pestering Stella, visiting daily and offering to do any odd job. And “half against his will,” Stella finally relented.

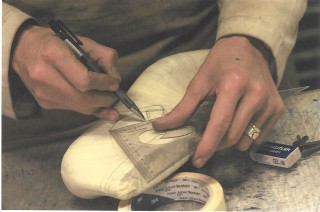

Fukaya started out making sketches and preparing pattern paper, and advanced to shoe repair. But the master had no time to teach the craft. Fukaya’s training, he recalls, consisted of “observing and stealing.”

Every evening, Fukaya would go home and experiment — imitating what he had seen Stella do in the daytime, absorbing the master’s technique through trial-and-error. He wasn’t paid during his year with Stella — and as his savings dwindled, he sometimes lived on one egg a day. But at the end of this peculiar apprenticeship, Fukaya was ready to try his hand as a shoemaker in Florence, home to some of Europe’s best.

Fukaya launched his brand “Il Micio” in 1999 and in 2003 was invited to design shoes for Tie Your Tie, a storied Florence gentleman’s store. Two years later he achieved his dream of opening his bespoke shoemaking shop on the discreet Via dei Federighi. But the closed nature of Florentine society was a barrier to success.

“When I opened the shop, people would dump garbage outside the door,” he recalls. “They would say, ‘What does a Japanese know about European shoemaking?'”

It took Fukaya years to find acceptance in Florence society and among the ranks of its great shoemakers. He won his place the same way he learned to speak Italian — not by going to school, but by engaging with people, meeting friends for an aperitivo, steeping himself in the local lifestyle.

“I think the most important thing is to become a part of the city’s family,” he says. “And I did so by having exchanges with the local people. It took time but I feel that today I’ve really been accepted as part of the family.”

He also says he formed a bond with Florentines through a shared love of monozukuri — the Japanese word for the art of making things. Fukaya collects antiques and is fascinated by craftsmanship from ages in which there were no machines. His own creations are made entirely with manual tools. And by delivering superior quality in shoemaking, Fukaya was able to win recognition.

“The people of Florence,” he explains, “will say, frankly, when a beautiful thing is beautiful. They will give it due respect.”

Beyond tradition, Fukaya said that in Italy he has found an ability to express himself creatively in ways that are difficult in Japan. “The things Japanese make in Japan are too perfect, they are lacking in some special flavor, touch,” he says. “Italy’s craftsmen also have high technical ability and make wonderful things, but … each one of them carries that person’s personality. This gives rise to an indescribable beauty, a sexiness.”

Culturally, Fukaya says he has also taken away lessons from the Italian way of life. “I have learned to take Saturdays and Sundays off,” he says.

“Cherishing family, making valuable time on weekends for family or just for yourself — I think that may be what’s good about Italian life.”

However, there are still some things about Italy that are hard to get used to: “Culture shock? The biggest one of all was seeing police officers on duty chatting up girls!”

Name: Hidetaka Fukaya

Profession: Shoemaker

Place of birth: Aichi Prefecture

Age: 42

Key moments in career:

1998 — Left Japan to learn Italian shoemaking

2005 — Achieved dream of opening a shoe shop at age 30

2015 — Named one of Italy’s 100 best artisans by Italia Su Misura project

Family: Wife Mieko and a 15-year-old black cat called Kuro

Words to live by: A sumo motto: “Heart, Technique, Physique”

Things you miss about Japan: Real Japanese food and real Japanese sake

Strengths: Monozukuri (making things)

Weaknesses: Desk work

“The cat is among the most beautiful creatures on Earth, both in form and movement,” Fukaya says. “And they don’t try to curry favor. The most important thing for me is to make customers happy, but as a craftsman it’s important to maintain my freedom of expression.”

It’s a philosophy that has helped Fukaya win respect and accolades in Italy’s secretive world of master craftsmen, with roots in Medieval guilds, in a city that is notorious for being one of the country’s most insular.

Today Fukaya commands prices of more than €3,000 (¥370,000) for a pair of made-to-order shoes, and creates readymade shoes for brands such as Japan’s Tomorrowland and Italy’s Tie Your Tie.

It has been a struggle reaching the top of his craft in a country that can be as tradition-bound as Japan. Fukaya was 24 when he left an enviable job in Tokyo as a designer for the Kensho Abe fashion label for the unknown world of fine Italian shoemaking. He did not speak a word of Italian.

The dream emerged by chance when he came across a book on Florentine artisans, and fell under the spell of the city’s shoemaking traditions. Since childhood, he had loved making things by hand — something he couldn’t do designing clothes — and suddenly decided that shoemaking was his calling.

“When I make a decision, I’m impatient to carry it out, that’s my personality — first just act, then think about it later,” Fukaya says. “So I just wanted to go to Italy, this feeling that I wanted to make shoes was so strong.”

But when Fukaya landed in Florence, there were no schools to teach him the craft. Today there are many Japanese studying Italian shoemaking — back in 1998, Fukaya was alone banging on the door of a closed-shop profession. He walked the streets of Florence, from shoemaker to shoemaker — a telephone book in hand — begging to be taken on as an apprentice. Each time the door was closed in his face. One day, a friend told him about the outstanding skill of a master shoemaker in the neighboring city of Siena. The encounter with Alessandro Stella’s handcrafted shoes, Fukaya recalls, was “love at first sight.” However, Siena is an even more insular city than Florence, and Stella refused to take Fukaya in. Undaunted, Fukaya kept pestering Stella, visiting daily and offering to do any odd job. And “half against his will,” Stella finally relented.

Fukaya started out making sketches and preparing pattern paper, and advanced to shoe repair. But the master had no time to teach the craft. Fukaya’s training, he recalls, consisted of “observing and stealing.”

Every evening, Fukaya would go home and experiment — imitating what he had seen Stella do in the daytime, absorbing the master’s technique through trial-and-error. He wasn’t paid during his year with Stella — and as his savings dwindled, he sometimes lived on one egg a day. But at the end of this peculiar apprenticeship, Fukaya was ready to try his hand as a shoemaker in Florence, home to some of Europe’s best.

Fukaya launched his brand “Il Micio” in 1999 and in 2003 was invited to design shoes for Tie Your Tie, a storied Florence gentleman’s store. Two years later he achieved his dream of opening his bespoke shoemaking shop on the discreet Via dei Federighi. But the closed nature of Florentine society was a barrier to success.

“When I opened the shop, people would dump garbage outside the door,” he recalls. “They would say, ‘What does a Japanese know about European shoemaking?'”

It took Fukaya years to find acceptance in Florence society and among the ranks of its great shoemakers. He won his place the same way he learned to speak Italian — not by going to school, but by engaging with people, meeting friends for an aperitivo, steeping himself in the local lifestyle.

“I think the most important thing is to become a part of the city’s family,” he says. “And I did so by having exchanges with the local people. It took time but I feel that today I’ve really been accepted as part of the family.”

He also says he formed a bond with Florentines through a shared love of monozukuri — the Japanese word for the art of making things. Fukaya collects antiques and is fascinated by craftsmanship from ages in which there were no machines. His own creations are made entirely with manual tools. And by delivering superior quality in shoemaking, Fukaya was able to win recognition.

“The people of Florence,” he explains, “will say, frankly, when a beautiful thing is beautiful. They will give it due respect.”

Beyond tradition, Fukaya said that in Italy he has found an ability to express himself creatively in ways that are difficult in Japan. “The things Japanese make in Japan are too perfect, they are lacking in some special flavor, touch,” he says. “Italy’s craftsmen also have high technical ability and make wonderful things, but … each one of them carries that person’s personality. This gives rise to an indescribable beauty, a sexiness.”

Culturally, Fukaya says he has also taken away lessons from the Italian way of life. “I have learned to take Saturdays and Sundays off,” he says.

“Cherishing family, making valuable time on weekends for family or just for yourself — I think that may be what’s good about Italian life.”

However, there are still some things about Italy that are hard to get used to: “Culture shock? The biggest one of all was seeing police officers on duty chatting up girls!”

Profile

Name: Hidetaka Fukaya

Profession: Shoemaker

Place of birth: Aichi Prefecture

Age: 42

Key moments in career:

1998 — Left Japan to learn Italian shoemaking

2005 — Achieved dream of opening a shoe shop at age 30

2015 — Named one of Italy’s 100 best artisans by Italia Su Misura project

Family: Wife Mieko and a 15-year-old black cat called Kuro

Words to live by: A sumo motto: “Heart, Technique, Physique”

Things you miss about Japan: Real Japanese food and real Japanese sake

Strengths: Monozukuri (making things)

Weaknesses: Desk work

- May 22, 2017

- Comment (0)

- Trackback(0)