▼ Kanji ‘Toilet Training’ Is a Hit With Kids

- Category:Event

One of the great incentives for learning Japanese is to appreciate the people’s rich sense of humor. I kid you not: Along with traditional performances such as 漫才 (manzai, comic dialogue) and 落語 (rakugo, traditional storytelling), the written and spoken language is full of outrageous ダジャレ (dajare, puns).

Japanese people also appreciate toilet humor — literally, as I recall in one particular case.

At my university, someone had scrawled 落書き (rakugaki, graffiti) in a cubicle in the men’s rest room that read: 汝、カミに見放された時は自らの手でウンを掴め (Nanji, kami ni mihanasareta toki wa mizukara no te de un o tsukame). Instead of あなた (anata, you), the writer used 汝 (nanji, the biblical “thou”), and from this it’s clear the passage was intended to reflect the style of Elizabethan English. The sentence might be translated as: “When thou findest thyself forsaken by the Lord, grasp thy fate in thine own hands.” But rather than writing out 神 (kami, god) and 運 (un, fate) in kanji characters, those two words appeared in katakana, signaling to the reader — as it often does — that mischief is afoot.

Kami also happens to be is a homonym for 紙 (kami, paper), and ウン (un) could also be short for うんこ (unko, excrement). In which case, the meaning changes to something more irreverent, like “When you find yourself without paper, then grab your s—- in your own hands.”

Such off-color humor has roots in remote antiquity. Back in the 15th century, for example, an unknown artist drew a scroll titled 放屁合戦 (Hōhi Gassen, “Farting Competition”) that depicted various men and women competing to see who could break wind the loudest. (For the curious, scenes from the scroll can be found online.)

And then came television. By the 1970s, scatological humor was combined with lowbrow slapstick as standard TV fare.

Purely out of sociocultural motivations you understand, every Saturday night I would tune in to TBS to watch a comedy team known as The Drifters in a variety program called 8時だヨ! 全員集合 (“Hachiji da Yo! Zen’in Shūgō,” “It’s 8 O’clock! Everybody Gather ‘Round”). For roughly an hour, it seemed the whole nation reverted to childhood, chuckling over the five-man group’s raunchy skits and juvenile pranks, many of which involved toilets, breaking wind, semi-indecent exposure and so on.

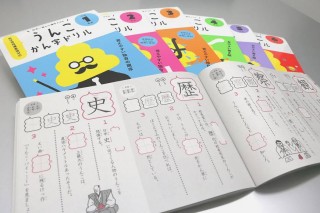

Now this year, the media is abuzz over a new series of workbooks for children titled うんこ漢字ドリル (Unko Kanji Doriru, “Poop Kanji Drills”). The books, authored by Yusaku Furuya, start from first grade and progressively introduce Sino-Japanese characters at elementary school level.

As a learning mnemonic, characters are creatively introduced using sentences related to defecation. It should be noted that as with its four-letter Anglo-Saxon equivalent, unko in colloquial usage can be used as a noun, or, by adding する (suru, to do), a verb.

To teach first-graders the kanji 花 (hana, flower), for example, page 50 has the student complete the sentence うんこのような花を見つけた (Unko no yō na hana o mitsuketa, “I found a flower that looks like poop”).

For the kanji 田 (den or ta, a rice field) on page 41, the student writes 田うえをしながら うんこをもらすおじいさん (taue o shinagara unko o morasu ojiisan, an old man who becomes incontinent while planting rice).

To learn the kanji for king on page 38, the student completes a sentence that reads 王さまは「うんこでしろを作れ」とめいれいした (Ōsama wa “Unko de shiro o tsukure” to meirei shita, “The king commanded, ‘Build a castle out of poop'”).

The wording on the book’s cover touts this teaching method as being 覚えやすい独自の順序 (oboeyasui dokuji no junjo, in an original order that’s easy to memorize) and 見やすい 書き順 (miyasui kakijun, easy-to-visualize writing order).

In any event, the series’ publisher, Bunkyosha, has really hit the jackpot:

Total sales so far are reported to have surpassed 2 million copies. And in its prestigious ヒット商品番付 (hitto shōhin banzuke, hit product rankings) for the first half of 2017, the Nikkei Marketing Journal of June 7 ranked the “Unko” book series in 6th place overall.

Writing in Shukan Taishu magazine (June 19), entertainer and commentator Terry Ito gives his thoughts on the “Unko”drill books’ popularity, remarking: うんこやオシッコ、 ちんちん、オナラなどの下ネタは、子どもたちの大好物。特に男の子には、鉄板ネタだ (Unko ya oshikko, chinchin, onara nado no shimoneta wa, kodomotachi no daikōbutsu. Toku ni otoko no ko ni wa, teppan neta da, “Kids love dirty words like poop, pee-pee, weenie, fart and so on. Especially for boys, it’s a surefire winner”).

He concludes: 単調になりがちな漢字の書き取りもこれなら楽しみながらできるということだ (Tanchō ni narigachi na kanji no kakitori mo kore nara tanoshiminagara dekiru to iu koto da, “With this, the often-boring task of transcribing kanji can also be enjoyable”).

In case Tsutomu-kun or Mariko-chan somehow get carried away by all this impish fun, the publisher wisely runs a disclaimer that states, 本書はお子様の不適切な行動を 助長することを意図しているものではありません (Honsho wa okosama no futekisetsu na kōdō o jochō suru koto o ito shite iru mono de wa arimasen, “This book is not intended to foster inappropriate behavior among children”).

Word on the street is that Bunkyosha may soon bank on its success with a similarly gross workbook aimed at assisting 数学の 苦手な子 (sūgaku no nigate na ko, mathematically challenged kids). This begs the question:

How long until the “Unko” series takes up the study of English? そんなことは考えたくもないです (Son’na koto wa kangaetaku mo nai desu, “I don’t even want to think about it”).

Japanese people also appreciate toilet humor — literally, as I recall in one particular case.

At my university, someone had scrawled 落書き (rakugaki, graffiti) in a cubicle in the men’s rest room that read: 汝、カミに見放された時は自らの手でウンを掴め (Nanji, kami ni mihanasareta toki wa mizukara no te de un o tsukame). Instead of あなた (anata, you), the writer used 汝 (nanji, the biblical “thou”), and from this it’s clear the passage was intended to reflect the style of Elizabethan English. The sentence might be translated as: “When thou findest thyself forsaken by the Lord, grasp thy fate in thine own hands.” But rather than writing out 神 (kami, god) and 運 (un, fate) in kanji characters, those two words appeared in katakana, signaling to the reader — as it often does — that mischief is afoot.

Kami also happens to be is a homonym for 紙 (kami, paper), and ウン (un) could also be short for うんこ (unko, excrement). In which case, the meaning changes to something more irreverent, like “When you find yourself without paper, then grab your s—- in your own hands.”

Such off-color humor has roots in remote antiquity. Back in the 15th century, for example, an unknown artist drew a scroll titled 放屁合戦 (Hōhi Gassen, “Farting Competition”) that depicted various men and women competing to see who could break wind the loudest. (For the curious, scenes from the scroll can be found online.)

And then came television. By the 1970s, scatological humor was combined with lowbrow slapstick as standard TV fare.

Purely out of sociocultural motivations you understand, every Saturday night I would tune in to TBS to watch a comedy team known as The Drifters in a variety program called 8時だヨ! 全員集合 (“Hachiji da Yo! Zen’in Shūgō,” “It’s 8 O’clock! Everybody Gather ‘Round”). For roughly an hour, it seemed the whole nation reverted to childhood, chuckling over the five-man group’s raunchy skits and juvenile pranks, many of which involved toilets, breaking wind, semi-indecent exposure and so on.

Now this year, the media is abuzz over a new series of workbooks for children titled うんこ漢字ドリル (Unko Kanji Doriru, “Poop Kanji Drills”). The books, authored by Yusaku Furuya, start from first grade and progressively introduce Sino-Japanese characters at elementary school level.

As a learning mnemonic, characters are creatively introduced using sentences related to defecation. It should be noted that as with its four-letter Anglo-Saxon equivalent, unko in colloquial usage can be used as a noun, or, by adding する (suru, to do), a verb.

To teach first-graders the kanji 花 (hana, flower), for example, page 50 has the student complete the sentence うんこのような花を見つけた (Unko no yō na hana o mitsuketa, “I found a flower that looks like poop”).

For the kanji 田 (den or ta, a rice field) on page 41, the student writes 田うえをしながら うんこをもらすおじいさん (taue o shinagara unko o morasu ojiisan, an old man who becomes incontinent while planting rice).

To learn the kanji for king on page 38, the student completes a sentence that reads 王さまは「うんこでしろを作れ」とめいれいした (Ōsama wa “Unko de shiro o tsukure” to meirei shita, “The king commanded, ‘Build a castle out of poop'”).

The wording on the book’s cover touts this teaching method as being 覚えやすい独自の順序 (oboeyasui dokuji no junjo, in an original order that’s easy to memorize) and 見やすい 書き順 (miyasui kakijun, easy-to-visualize writing order).

In any event, the series’ publisher, Bunkyosha, has really hit the jackpot:

Total sales so far are reported to have surpassed 2 million copies. And in its prestigious ヒット商品番付 (hitto shōhin banzuke, hit product rankings) for the first half of 2017, the Nikkei Marketing Journal of June 7 ranked the “Unko” book series in 6th place overall.

Writing in Shukan Taishu magazine (June 19), entertainer and commentator Terry Ito gives his thoughts on the “Unko”drill books’ popularity, remarking: うんこやオシッコ、 ちんちん、オナラなどの下ネタは、子どもたちの大好物。特に男の子には、鉄板ネタだ (Unko ya oshikko, chinchin, onara nado no shimoneta wa, kodomotachi no daikōbutsu. Toku ni otoko no ko ni wa, teppan neta da, “Kids love dirty words like poop, pee-pee, weenie, fart and so on. Especially for boys, it’s a surefire winner”).

He concludes: 単調になりがちな漢字の書き取りもこれなら楽しみながらできるということだ (Tanchō ni narigachi na kanji no kakitori mo kore nara tanoshiminagara dekiru to iu koto da, “With this, the often-boring task of transcribing kanji can also be enjoyable”).

In case Tsutomu-kun or Mariko-chan somehow get carried away by all this impish fun, the publisher wisely runs a disclaimer that states, 本書はお子様の不適切な行動を 助長することを意図しているものではありません (Honsho wa okosama no futekisetsu na kōdō o jochō suru koto o ito shite iru mono de wa arimasen, “This book is not intended to foster inappropriate behavior among children”).

Word on the street is that Bunkyosha may soon bank on its success with a similarly gross workbook aimed at assisting 数学の 苦手な子 (sūgaku no nigate na ko, mathematically challenged kids). This begs the question:

How long until the “Unko” series takes up the study of English? そんなことは考えたくもないです (Son’na koto wa kangaetaku mo nai desu, “I don’t even want to think about it”).

- June 19, 2017

- Comment (0)

- Trackback(0)