▼ Private Schooling Booms In Japan And South Korea Fuel Inequality

- Category:Other

'Premium education' enriches minds but puts governments across Asia to the test

TOKYO -- For the children of ambitious Japanese parents, competition begins well before the first day of elementary school.

"Please finish before the hand turns four," says the teacher, pointing to a clock. Roughly 20 kids, most of them 4 or 5 years old, sit on the floor in small groups with a big piece of blank paper and a task: drawing an imaginary animal. As they start discussing the size of the ear or which colors to use, the staff behind them jot down notes on clipboards. Are they actively engaging? Do they remember the instructions?

The children are preparing for an exam to get into one of the top private elementary schools in Tokyo. Shingakai, a unit of private education company Riso Kyoiku, has been offering such lessons for six decades. But there have been some significant changes in recent years -- the majority of the kids' mothers are working, and the country is suffering a decline in births.

For reasons that are not always obvious, these factors are fueling demand for "premium education." But neighboring South Korea may offer a cautionary tale of how a rush into high-priced schooling can lead to astronomical expenses, exacerbate social inequality and even fuel a demographic crisis.

"The birthrate is declining, so getting into a good university is hard. Securing a good education from early on is crucial," said Megumi, the CEO of an online apparel company and a mother of four. She has sent two of her children to Shingakai; her 4-year-old daughter now attends Shinga's Club, a nursery chain run by Shingakai that incorporates exam preparation methods.

While it may seem counterintuitive that fewer young people will make university applications more competitive, there is logic to the thinking of parents like Megumi.

For many couples, having only one or two children frees up money to invest more in education, which they hope will put their kids on a path to the nation's top schools. So although it may be easier for young generations to get into colleges in general, more applicants may end up trying to squeeze into the best ones. High-quality early childhood education is seen as a chance to gain an edge.

While Megumi's family is relatively large, she and her husband are willing, able and convinced they need to pay the hefty price. A high-end nursery or private classes can cost easily $1,000 per month, more than three times what is considered the average. But children are flooding in -- Shingakai said the student body at the end of February was up 17.3% from a year earlier.

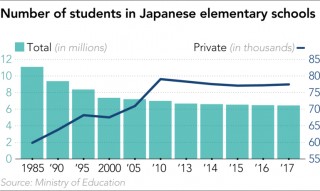

Across Japan, 77,453 students were enrolled in private elementary schools in 2017, up 15% from 2000. Total elementary school students, on the other hand, had fallen 12% to 6.44 million.

As a businesswoman, Megumi herself represents another driver of the trend. Heightened interest in childhood education in Japan coincides with the rising status of women, according to Naoko Kuga, senior researcher at NLI Research Institute.

In 1996, the ratio of Japanese women entering four-year universities overtook that of shorter-term colleges, which were once considered more suitable for women because most jobs available to them were administrative. "Modern-day mothers are from a generation that went through education without having to think about gender, which is fueling the passion for education," Kuga said.

Double-income households, of course, also tend to have more cash to spend. What they lack are hours in the day.

Enter professionals like Rina Hatano, a Tokyo consultant who advises parents on the exams and even attends school events on their behalf. Her assistance is part of a growing range of flexible services that help working mothers put their kids on the elite track.

"Double-income households don't have time to prepare children for exams," Hatano said. "But many have high expectations for their children. We want to bridge the gap."

While advocates applaud the greater focus on schooling, critics say the trend signals growing inequality in multiple ways. For one, private schools are concentrated in major cities. "Parents living in metropolitan areas simply have more options," said Yuki Mochizuki, a professor at Nihon University. "It can lead to regional disparities."

And just because families live in the right place does not mean they can afford the luxury. One industry executive said placing a child in nurseries like Shinga's Club full-time is unrealistic for households earning less than 15 million yen ($135,000) a year, nearly three times the national average.

Kuga warned educational inequality can rise over the long run because high-income earners tend to marry spouses with a similar status.

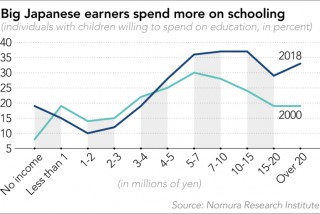

One-third of individuals earning more than 20 million yen annually said they would like to actively spend money on their children's education, up from 19% in 2000, according to a survey by the Nomura Research Institute. Conversely, the ratio for those earning 1 million to 2 million yen fell from 14% to 10%.

Enter professionals like Rina Hatano, a Tokyo consultant who advises parents on the exams and even attends school events on their behalf. Her assistance is part of a growing range of flexible services that help working mothers put their kids on the elite track.

"Double-income households don't have time to prepare children for exams," Hatano said. "But many have high expectations for their children. We want to bridge the gap."

While advocates applaud the greater focus on schooling, critics say the trend signals growing inequality in multiple ways. For one, private schools are concentrated in major cities. "Parents living in metropolitan areas simply have more options," said Yuki Mochizuki, a professor at Nihon University. "It can lead to regional disparities."

And just because families live in the right place does not mean they can afford the luxury. One industry executive said placing a child in nurseries like Shinga's Club full-time is unrealistic for households earning less than 15 million yen ($135,000) a year, nearly three times the national average.

Kuga warned educational inequality can rise over the long run because high-income earners tend to marry spouses with a similar status.

One-third of individuals earning more than 20 million yen annually said they would like to actively spend money on their children's education, up from 19% in 2000, according to a survey by the Nomura Research Institute. Conversely, the ratio for those earning 1 million to 2 million yen fell from 14% to 10%.

Premium education, right up through high school, is even more entrenched in South Korea -- where the birthrate is at a nearly five-decade low.

Starting in the first year of high school, a practice called "spec management" is considered essential for getting into the medical department at Seoul National University. Students are at pains to ensure they have the right "specifications."

This, in turn, has given rise to a market for "business coordinators" who not only monitor students' schoolwork but also guide their reading and extracurricular activities. To show the university that a student is willing to do whatever it takes to be a doctor, for example, a coordinator would have the student participate in medical-related club activities.

Coordinators even summarize popular books for their students.

These services do not come cheap. The cost can run to about 100 million won ($87,000) a year, but one popular coordinator said "demand is strong from doctors who want to pass on the practice to their children."

A South Korean TV drama that centered on the coordinator business scored record ratings. The show, broadcast until February, was called "SKY Castle" -- SKY being an acronym for the prestigious trinity of Seoul National University, Korea University and Yonsei University. It told the tale of parents who entrusted their children to a cruel coordinator. And although it was meant as a warning against an extreme focus on spec management, the popular coordinator said inquiries actually increased.

South Korea's Ministry of Education says the average cost of private education is 321,000 won per high school student per month. But many parents are paying far more. "In Daechi-dong, 2 million to 5 million won a month is normal," said one. Even for employees of major conglomerates, education expenses can easily eat up half a month's salary.

The high cost of education is believed to be contributing to South Korea's birth crisis, as couples fear the burden. The total fertility rate, which measures how many children the average woman would have in her lifetime, fell to 0.98 births in 2018, the lowest reading since 1970.

The government spent 117 trillion won from 2016 to 2018 to tackle the declining birthrate and aging population. Yet, instead of boosting the rate to the target of 1.5, the campaign did little to prevent a further downward spiral.

South Korea's Ministry of Education says the average cost of private education is 321,000 won per high school student per month. But many parents are paying far more. "In Daechi-dong, 2 million to 5 million won a month is normal," said one. Even for employees of major conglomerates, education expenses can easily eat up half a month's salary.

The high cost of education is believed to be contributing to South Korea's birth crisis, as couples fear the burden. The total fertility rate, which measures how many children the average woman would have in her lifetime, fell to 0.98 births in 2018, the lowest reading since 1970.

The government spent 117 trillion won from 2016 to 2018 to tackle the declining birthrate and aging population. Yet, instead of boosting the rate to the target of 1.5, the campaign did little to prevent a further downward spiral.

Skeptics question whether Japan's measures will fare much better.

In October, Japan is to introduce free admission to accredited nursery schools and kindergartens for all children between the ages of 3 and 5.

Low-income families will also be able to send children up to 2 years old to day care for free. While these steps are supposed to relieve the financial pressure on parents, inequality is likely to persist due to a chronic shortage of teachers and affordable nurseries.

A bigger question may be how to promote adult education and shore up the labor pool. The Japanese government is promoting "recurrent education," in which mothers who left work to raise children or retirees go back to school before re-entering the workforce. But few are taking the opportunity to bolster their skills, fearing they will not be able to secure jobs that will pay enough to recoup the tuition fees.

In the meantime, divisions are widening in Japan's "all middle-class society."

During the postwar economic boom of the 1970s, most Japanese proudly identified themselves as middle class. On the surface, this is still true: A government survey in 2017 found that more than 90% said they were upper-middle, lower-middle or middle class. But a closer look reveals a creeping disparity. The percentage of people who identified themselves as upper-middle class rose in big cities, while more respondents in small cities simply said middle class.

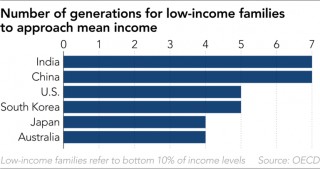

In one measure of how easily people can move up the income ladder, it takes an average of four generations for low-income Japanese families to approach the mean income, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. That is one generation faster than South Korea and the U.S., but the pace of advancement lags behind some European countries. In Japan's case, the OECD cites high income inequality as a negative factor.

"The wealthy are becoming wealthier while it is getting tougher for low-income households," Nihon University's Mochizuki said. "The gap is widening."

Young families in China, Singapore and other rising Asian economies face a similar plight. In China, it takes an average of seven generations for low-income families to approach the mean income, according to the OECD. Chinese analysts suggest that income and education inequality are mutually reinforcing factors that perpetuate their own vicious cycle.

Parents who can afford premium education, naturally, want to give their children every advantage to cope with an uncertain future. But for the governments in Asia, inequality of educational opportunity poses a real challenge, and time is not on their side.

Nikkei staff writer Sotaro Suzuki in Seoul contributed to this article.

In October, Japan is to introduce free admission to accredited nursery schools and kindergartens for all children between the ages of 3 and 5.

Low-income families will also be able to send children up to 2 years old to day care for free. While these steps are supposed to relieve the financial pressure on parents, inequality is likely to persist due to a chronic shortage of teachers and affordable nurseries.

A bigger question may be how to promote adult education and shore up the labor pool. The Japanese government is promoting "recurrent education," in which mothers who left work to raise children or retirees go back to school before re-entering the workforce. But few are taking the opportunity to bolster their skills, fearing they will not be able to secure jobs that will pay enough to recoup the tuition fees.

In the meantime, divisions are widening in Japan's "all middle-class society."

During the postwar economic boom of the 1970s, most Japanese proudly identified themselves as middle class. On the surface, this is still true: A government survey in 2017 found that more than 90% said they were upper-middle, lower-middle or middle class. But a closer look reveals a creeping disparity. The percentage of people who identified themselves as upper-middle class rose in big cities, while more respondents in small cities simply said middle class.

In one measure of how easily people can move up the income ladder, it takes an average of four generations for low-income Japanese families to approach the mean income, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. That is one generation faster than South Korea and the U.S., but the pace of advancement lags behind some European countries. In Japan's case, the OECD cites high income inequality as a negative factor.

"The wealthy are becoming wealthier while it is getting tougher for low-income households," Nihon University's Mochizuki said. "The gap is widening."

Young families in China, Singapore and other rising Asian economies face a similar plight. In China, it takes an average of seven generations for low-income families to approach the mean income, according to the OECD. Chinese analysts suggest that income and education inequality are mutually reinforcing factors that perpetuate their own vicious cycle.

Parents who can afford premium education, naturally, want to give their children every advantage to cope with an uncertain future. But for the governments in Asia, inequality of educational opportunity poses a real challenge, and time is not on their side.

Nikkei staff writer Sotaro Suzuki in Seoul contributed to this article.

- May 16, 2019

- Comment (3677)

- Trackback(0)

Comment(s) Write comment

ivermectin tablets order <a href="https://showstromectolby.com/ ">ivermectin price usa</a>

-

AmsmNulajagma Web Site

- March 29, 2022

ivermectin 1 <a href="https://stromectolons.com/ ">ivermectin pill cost</a>

-

Kbvsaisa Web Site

- March 29, 2022

stromectol medication <a href="https://stromectolons.com/ ">cost of stromectol</a>

-

Kbvsaisa Web Site

- March 29, 2022

ivermectin generic <a href="https://showstromectolby.com/ ">stromectol ivermectin buy</a>

-

AmsmNulajagma Web Site

- March 29, 2022

stromectol lotion <a href="https://itstromectoldg.com/ ">ivermectin 0.08</a>

-

FehhAmows Web Site

- March 29, 2022

stromectol ivermectin tablets <a href="https://stromectoldm.com/ ">ivermectin uk buy</a>

-

Rkjgaima Web Site

- March 29, 2022

ivermectin cost canada <a href="https://stromectoldm.com/ ">ivermectin price uk</a>

-

Rkjgaima Web Site

- March 29, 2022

ivermectin 5 mg price <a href="https://edstromectolzg.com/ ">ivermectin lotion</a>

-

CrgbBries Web Site

- March 29, 2022

ivermectin canada <a href="https://stromectoldm.com/ ">ivermectin 6</a>

-

Rkjgaima Web Site

- March 29, 2022

ivermectin 1 topical cream <a href="https://itstromectoldg.com/ ">where to buy ivermectin</a>

-

FehhAmows Web Site

- March 28, 2022

ivermectin 80 mg <a href="https://itstromectoldg.com/ ">ivermectin 3mg price</a>

-

FehhAmows Web Site

- March 28, 2022

purchase stromectol <a href="https://itstromectoldg.com/ ">ivermectin canada</a>

-

FehhAmows Web Site

- March 28, 2022

ivermectin 9 mg tablet <a href="https://showstromectolby.com/ ">ivermectin 0.5%</a>

-

AmsmNulajagma Web Site

- March 28, 2022

ivermectin buy nz <a href="https://stromectolons.com/ ">ivermectin ebay</a>

-

Kbvsaisa Web Site

- March 28, 2022

Kbvsaisa Web Site- March 29, 2022