▼ Japan's Cutthroat School System: A Cautionary Tale for the U.S.

- Category:Other

THE ATLANTIC

"No Child Left Behind." "Race to the Top." The names suggest mobility, progress, moving on up and not falling back. The goal of education, according to these national education initiatives with their standards and testing, is forward motion and competitive advantage, progress and success, both in an unabashedly economic context. President Obama talks about how we need to "invest in our young people" in order to compete in a global marketplace. Bill Gates, too, argues we need standards in order to become "more competitive as a country."

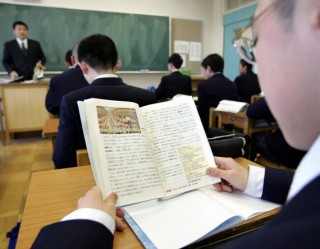

In this, as in so many other things, Japan preceded us. In her new book, Precarious Japan, anthropologist Anne Allison returns to the Japanese education system that she discussed in some detail in her 1995 monograph Permitted and Prohibited Desires. As Allison says in both volumes, the Japanese education system after World War II was built around highly competitive and rigorous high-school testing, which required enormous discipline and study.

The goal was to prepare students for equally arduous employment in Japan's industrial capitalist economy, where men worked basically all the time. (In Precarious Japan, Allison relates one anecdote of a man sleeping at his desk for no extra pay.) Good scores on tests ensured good jobs in Japan's corporate economy. For their part, Allison writes, Japanese women were expected to stay home and focus all their time and energy on preparing children for their exams. In Allison's words, they "worked hard at love." Family, school, and work thus fit into a single seamless system of economic striving that "catapulted Japan to the heights of global prestige as an industrial power."

Again, in many ways, the Japanese experience seems to echo the dream of education reformers and policy-makers in the United States: strong parental involvement, rigorous testing, discipline, and study in school leading to disciplined workers competing successfully in the global economy. Obviously, every detail isn’t as appealing as every other. The relegation of women to the domestic sphere would not be popular in the U.S., for example. But overall, Japan's system can be seen as a prototype; the dream we Americans are now striving for.

The one problem being, as Allison shows, that that dream has already turned to dung. Japan's bubble economy burst in the ‘90s. Its amazing, decades-long post-war economic boom turned into post-post-war economic stagnation. Precarious Japan chronicles the unraveling of the home/job/school unity on which Japanese capitalism was based. Through a combination of economic contraction and neo-liberal restructuring of the economy, the lifetime salaryman jobs which were to be the reward of success in high school dried up. Today one-third of Japanese workers are irregularly employed, including 70 percent of all female workers and half of all workers between 15 and 24. A full 77 percent of the irregularly employed earn wages less than poverty level, and so are working poor.

There are a couple possible lessons to take from Japan's experience. On the one hand, you could perhaps argue that it shows that test-oriented education does not actually promote global competitiveness; that Japan's focus on testing and rigid connections between school, home and family, stifled creativity and created an insufficiently flexible economy. This is the critique that University of Oregon Professor Yong Zhao makes of our emphasis on testing in the U.S. From his perspective, the goal of global competitiveness is the right goal, but to get there we need education that focuses on creativity and innovation rather than test-taking.

Perhaps though the problem, though, is not with the methods we are using to link education to economic advancement, but linking education and economic advancement in the first place. Uncertain work and falling wages have contributed to the precariousness in Japan that Allison discusses, but they aren't its only cause. Rather, she suggests, the unified emphasis on economic achievement and global advancement as the social purpose has left people with few resources with which to confront hard times. The path from family to school to corporation in the context of expanding capitalism underwrote people's social place to such an extent that without it, many individuals become placeless.

In this context, Allison talks at some length about the Japanese social phenomenon of hikikomori, which began to emerge in the early 1990s. Hikikomori are effectively non-spiritual late capitalist monks; male young adults who "withdraw and remain in a single room they rarely, if ever, leave," sometimes for years. Generally hikiomori are isolated in their family homes and remain dependent for minimal care on their parents, who they may not even interact or speak with. Estimates of the number of hikikomori range between 100,000 and 700,000.

Close to a third of them start out as kids who refuse to go to school. One hikikomori Allison talks to named Kacco says, "As long as I performed well in school, things were okay. But once I started to deviate just a little—they [parents, teachers] went to the extreme and started treating me incredibly coldly." Kacco adds, "now as the economy has fallen, we've all become strangers to one another. Society today is very cold." Allison discusses this coldness in other contexts: the isolation and abandonment of many elderly people; the disconnected lives of the growing ranks of part-time workers, many of whom have no permanent residence but go from net-café to net-café, logging on to seek the next days employment.

The Japanese school system oriented fanatically towards capitalist achievement seems to have reproduced or helped create capitalist social atomization. The notorious bullying in Japanese schools has actually been seen by many parents and teachers as a feature not a bug. Students can be targeted for failing to do well academically (Allison discusses one girl bullied for her failure to learn kanji quickly enough.) "[T]he parent who refuses to pamper their bullied child…, thereby forcing them to become tough as nails, is something of a Japanese ideal," Allison writes. "Tough love," she adds, leads to toughness and success, "Japan as number one."

Again, though, that link between competitive schooling and Japanese triumph has broken apart over the last decades. In light of that, and of our own protracted ongoing experience with economic precariousness, it might be worthwhile for the U.S. to reconsider our current focus on schools as engines of economic attainment, either individual or national. Do we want all our students constantly rushing in a race to the top, even if, life being what it is, that top is sometimes not a mountain but a cliff? Is education entirely about succeeding economically? Or might there be other, more important kinds of success, involving connection, community, and rootedness? Both Japan and the U.S. could stand to think about whether we want to concentrate on getting schools to produce good workers, or whether we would rather have them help to make good human beings.

- December 21, 2015

- Comment (0)

- Trackback(0)