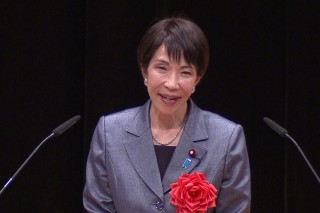

Japanese Prime Minister

Sanae Takaichi on Wednesday expressed hopes of deepening her relationship with U.S. President Donald Trump and strengthen cooperation between the two countries in rare earths development and other areas of economic security when she visits Washington next month.

Takaichi, at a news conference late Wednesday, expressed hopes to strengthen cooperation with the U.S., especially in economic security, as tensions between Tokyo and Beijing have risen over the last few months.

Takaichi, elected as Japan’s first female leader in October, was reappointed by Parliament as prime minister earlier in the day and formed her second Cabinet, following a landslide

election win last week.

Her goals include an increase in military power, more government spending and ultra-conservative social policies.

Takaichi aims to use the mandate she got in the election to boost her ruling Liberal Democratic Party as it looks to capitalize on a two-thirds supermajority in the lower house, the more powerful of Japan’s two parliamentary chambers.

The power of a supermajority

Having two-thirds control of the 465-seat lower house allows Takaichi’s party to dominate top posts in house committees and push through bills rejected by

the upper house, the chamber where the LDP-led ruling coalition lacks a majority.

Takaichi wants to bolster

Japan’s military capability and arms sales, tighten

immigration policies, push

male-only imperial succession rules and preserve a criticized tradition that pressures women into abandoning their

surnames.

Her ambition to revise the U.S.-drafted postwar pacifist Constitution might have to wait, for now, as she is facing pressure to deal with rising prices, a declining population and worries about military security.

Addressing rising prices

Her first urgent task is to address rising prices and sluggish wages and pass a budget bill to fund those measures, delayed by the election.

Takaichi proposes a two-year sales tax cut on food products to ease household living costs. She told

Experts caution that her liberal fiscal policy could drive up prices and delay progress on trimming Japan’s huge national debt.

Courting Trump

Takaichi is maneuvering for a crucial summit next month with Trump, who will visit Beijing in April.

The U.S. president endorsed Takaichi ahead of the Japanese election, and hours before Takaichi’s reappointment as prime minister, U.S. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick announced Japan will provide capital for three projects under a

$550 billion investment package that Japan pledged in October.

Japan is committed to the $36 billion first batch of projects — a natural gas plant in Ohio, a U.S. Gulf Coast crude oil export facility and a synthetic diamond manufacturing site.

Takaichi said she hoped to “closely cooperate” with Trump in the first investment inititives at the talks scheduled for March 19.

Japan is also under pressure to increase annual defense spending.

”Japan will keep spending more and more for the U.S. ... The question is whether the public wants her to speak out against Trump or be obedient to ensure Japanese security,” said Masato Kamikubo, a Ritsumeikan University professor of policy science.

“For China, it’s simple. Japanese people want her to be tough.”

A hawk on China

Takaichi in November suggested possible Japanese action if China makes a military move against Taiwan, the self-governing island that Beijing claims as its own. That has led to

Beijing’s diplomatic and economic reprisals.

Many Japanese, frustrated by China’s growing assertiveness, welcomed her comments on Taiwan.

Emboldened by the big election win, Takaichi could take a more hawkish stance with China, experts say.

Takaichi, soon after the election, said she is working to gain support for a visit to Tokyo’s controversial

Yasukuni Shrine. Visits to the shrine are seen by Japan’s neighbors as evidence of a lack of remorse for Japan’s wartime past.

A stronger military that spends more and sells more

Takaichi has pledged to

revise security and defense policies by December to bolster Japan’s military capabilities, lifting a ban on lethal weapons exports and moving further away from postwar pacifist principles.

Japan is also considering the development of a nuclear-powered submarine to increase offensive capabilities.

Takaichi wants to improve intelligence-gathering and establish a national agency to work more closely with ally Washington and defense partners like Australia and Britain.

She supports a controversial anti-espionage law that largely targets Chinese spies. Some experts say it could undermine Japanese civil rights.

Stricter on immigration and foreigners

Takaichi has proposed tougher policies on immigration and foreigners, something that resonates with a growing frustration in Japan.

Her government in January approved tougher rules on permanent residency and naturalization as well as measures to prevent unpaid tax and social insurance.

Promoting traditional family values

Takaichi supports the imperial family’s male-only succession and opposes same-sex marriage.

She is also against a revision to the 19th-century civil law that would allow separate surnames for married couples so that women don’t get pressured into abandoning theirs.

In a step that rights activists call an attempt to block a dual-surname system, Takaichi is calling for a law to allow the greater use of maiden names as aliases instead.