Japan has restarted operations at the world's largest nuclear power plant for the first time since the 2011 Fukushima disaster forced the country to shut all of its reactors.

The decision to restart reactor number 6 at Kashiwazaki-Kariwa north-west of Tokyo was taken despite local residents' safety concerns.

It was delayed by a day because of an alarm malfunction and is due to begin operating commercially next month.

Heavily reliant on energy imports, Japan was an early adopter of nuclear power. But in 2011 all 54 of Japan's reactors had to be shut after the most powerful earthquake it had ever recorded triggered a meltdown at Fukushima, causing one of the worst nuclear disasters in history.

This is the latest installment in Japan's nuclear power reboot, which still has a long way to go.

The seventh reactor at Kashiwazaki-Kariwa is not expected to be brought back on until 2030, and the other five could be decommissioned. That leaves the plant with far less capacity than it once had when all seven reactors were operational: 8.2 gigawatts.

The meltdown at Fukushima Daiichi, 220km (135 miles) north-east of Tokyo on the coast, led to radioactive leakage. Local communities were evacuated, and many have not returned despite official assurances that it was safe to do so.

Critics say the plant's owner Tokyo Electric Power Company, or Tepco, was not prepared, and the response from them and government was not well co-ordinated. An independent government report called it a "man-made disaster" and blamed Tepco, although a court later cleared three of their executives of negligence.

Still the fear and lack of trust fuelled public opposition to nuclear power and Japan suspended all of its reactors.

It has now spent the past decade trying to wake up those power plants, as it seeks to reach net zero emissions by 2050.

Since 2015, Japan has restarted 15 out of its 33 operable reactors. The Kashiwazaki-Kariwa plant is the first of those owned by Tepco to be turned back on.

Before 2011, nuclear power accounted for nearly 30% of Japan's electricity and the country planned to get that up to 50% by 2030. Its energy plan last year unveiled a tamer goal: it wants nuclear power to provide 20% of its electricity needs by 2040.

Even that may be tricky.

'A Drop On A Hot Stone'

Global momentum is building around nuclear energy, with the International Atomic Energy Agency estimating that the world's nuclear power capacity could more than double by 2050. In Japan, as of 2023, nuclear power accounted for just 8.5% of electricity.

Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, who took office in October, has emphasised the importance of nuclear power for Japan's energy self-sufficiency. Especially as it expects energy demand to surge because of data centres and semiconductor manufacturing.

Japan's leaders and its energy companies have long pushed for nuclear power. They say it's more reliable than renewable energy like solar and wind, and better suited for Japan's mountainous terrain. But critics say the emphasis on nuclear energy has come at the cost of investing in renewables and cutting emissions.

Now, as Japan tries to revive its nuclear power ambitions, the costs of running the reactors have surged, partly because of new safety checks that require hefty investments from companies trying to restart plants.

"Nuclear power is getting much more expensive than they ever thought it would," says Dr Florentine Koppenborg, a senior researcher at the Technical University of Munich.

The government could subsidise the costs, or pass them on to consumers - both unpalatable options for Japan's leaders, who have for decades been hailing the affordability of nuclear power. An expensive energy bill could also hurt the government at a time when households are protesting about rising costs.

The government's "hands are tied when it comes to financially supporting nuclear power, unless it's willing to go back on one of the main selling points", Koppenborg says.

"I think [Japan's nuclear power revival] is a drop on a hot stone, because it does not change the larger picture of nuclear power decline in Japan."

Beyond the fear of another disaster like Fuksuhima, a series of scandals has also rattled public trust.

The Kashiwazaki-Kariwa plant in particular found itself embroiled in a couple of them. In 2023, one of its employees lost a stack of documents after placing it on top of their car and forgetting it was there before driving away. In November, another was found to have mishandled confidential documents.

A Tepco spokesperson said the company reported the incidents to the Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA), adding that it aimed to continue improving security management.

These revelations are "a good sign" for transparency, says Koppenborg. But they also reveal that "Tepco is struggling to change its ways [and] the way it approaches safety".

Earlier this month, the NRA suspended its review to restart nuclear reactors at Chubu Electric's Hamaoka plant in central Japan, after the company was found to have manipulated quake data in its tests.

The company apologised, saying: "We will continue to respond sincerely, and to the fullest extent possible, to the instructions and guidance of the NRA."

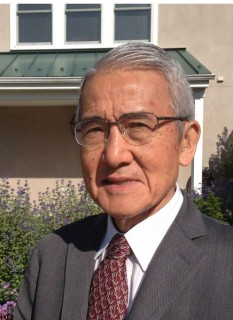

Hisanori Nei, a former senior nuclear safety official, tells the BBC, while he was "surprised" by the scandal at Hamaoka, he believed the harsh penalty handed to its operator should deter other companies from doing the same.

"Power companies should recognise the importance not to [falsify data]," he said, adding that authorities will "reject and punish" offending companies.

Surviving Another Fukushima

What happened at Fukushima turned Japanese public opinion against what had been hailed as an affordable and sustainable form of energy.

Thousands of residents filed class action lawsuits against Tepco and the Japanese government, demanding compensation for property damage, emotional distress and health problems allegedly linked to radiation exposure.

In the weeks after the March 2011 disaster, 44% of Japanese thought the use of nuclear power should be reduced, according to a survey by Pew Research Center. That figure jumped to 70% by 2012. But then polls by the Japanese business publication Nikkei in 2022 showed that more than 50% of people supported nuclear power if safety was ensured.

But there is still fear and mistrust. In 2023, the release of treated radioactive water from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant

sparked anxiety and anger both at home and abroad.

And many remain opposed to restarting nuclear plants. In December, hundreds of protesters gathered outside the Niigata prefectural assembly where Kashiwazaki-Kariwa is located, voicing safety concerns.

"If something was to happen at the plant, we would be the ones to suffer the consequences," one protester told Reuters news agency.

Last week, ahead of Kashiwazaki-Kariwa's restart, a small crowd gathered in front of Tepco's headquarters to protest again.

Nuclear safety standards have been ramped up after Fukushima. The NRA, a cabinet body established in 2012, now oversees the restarting of the country's nuclear plants.

At Kashiwazaki-Kariwa, 15-metre-high (49-foot) seawalls have been built to guard against large tsunamis; watertight doors now protect critical equipment at the facility.

"Based on the new safety standards, [Japan's nuclear plants] could survive even a similar earthquake and tsunami like the one we had in 2011," says Nei, the former senior nuclear safety official.

But what worries Koppenborg is: "They're preparing for the worst they've seen in the past but not for what is to come."

Some experts worry that these policies are not planning enough to account for rising sea levels due to climate change, or the once-in-a-century megaquake that Japan has been anticipating.

"If the past repeats itself, Japan is super well-prepared," Koppenborg says. "If something really unexpected happens and a bigger than expected tsunami comes along, we don't know."